Expert Articles

Taxation of Virtual Digital Assets - A Primer

Need for recognizing and taxing Income from VDAs:

The world has witnessed massive growth in demand for and transactions in cryptocurrencies, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and other digital assets. These digital assets have attracted several investors around the globe. This outlook of investors in digital assets have led to an increased demand and trade of digital assets, thereby resulting into exponential value appreciation and in turn the value of digital assets.

Specifically, when we talk about the cryptocurrencies, there are several thousands of cryptocurrencies in circulation; inter alia, Bitcoin and Ethereum being the top 2 cryptocurrencies in terms of market share. Presently, the global crypto market is of USD 1.06 trillion. Likewise, according to the report of ‘Market Decipher’, the global market size of NFT itself is estimated to be at USD 232 Million, as in the year 2020 and subsequently, is expected to grow 3 times of its current size by the year 2031. According to certain reports, India tops the chart of countries with most cryptocurrency holders in the world, with cryptocurrency investment of approximately USD 6.6 billion, as of May 2021.

Many countries have denied recognizing cryptocurrencies as legal tender and have either banned them or have imposed strict regulations against their usage and acceptability. However, interestingly, a country like El-Salvador has recognized “Bitcoin” as their legal tender. Further several countries have recognized cryptocurrencies and other digital investments as assets.

Accordingly, due to Indian population’s huge investment in cryptocurrency, NFTs and other digital assets as well, the Government of India (GOI), in its Finance Act 2022, recognized and introduced taxation of a new class of asset under The Income Tax Act, 1961 (hereinafter referred as “the Act”), 1961, called as VDAs.

What does VDA Include?

The definition of VDA as given under section 2(47) of the Act, is an inclusive definition. However, the Central Government may, vide a notification, exclude any digital asset from the definition of VDA.

VDA as defined under the Act inter alia, includes:

A. Any cryptographically generated Information/Code/Number/token

- not being Indian or foreign,

- having an exchange value represented in digital form,

- exchanged with or without consideration,

- with the promise or representation of having inherent value; or

- functions as a store of value or a unit of account,

- that may be used in any financial transaction or investment,

- and can be transferred, stored, or traded electronically.

B. NFT or any other token of similar nature; or

C. Any other digital asset as may be notified by Central Government[1].

Digital asset excluded from the definition of VDA

The Central Government has excluded following digital assets from the definition of VDA through a notification[2]:

- Gift card or vouchers that may be used to obtain goods or services or discounted goods or services;

- Mileage points, reward points or loyalty cards without monetary consideration and that may be used only to obtain goods or services or discounted goods or services;

- Subscription to website or platforms or application; or

- Any NFT backed by an underlying tangible asset where transfer of such NFT results in legally enforceable transfer of ownership of such tangible asset.

How will the Income from VDA be taxed?

The Finance Act, 2022 has inserted Section 115BBH in the Act to bring VDA under tax.

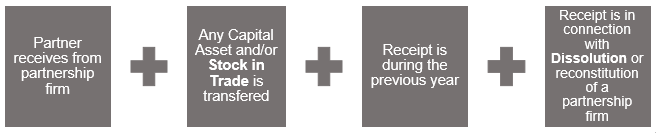

As per the calculation of gain on transfer method given under Section 115BBH, there is a metaphoric representation of taxing of gains arising upon transfer of VDA similar to that on transfer of any other capital asset. However, the law has not restricted the nature of holding of VDA to a “Capital Asset” alone. Hence, any gain on transfer of VDA held as stock-in-trade or otherwise shall also be taxed as per the provisions of Section 115BBH.

Further, any VDA received against no or low consideration would be taxed in the hands of recipient as ‘’Income from Other Sources’’, as per the specific provisions of section 56(2)(x) of the Act.

Calculation of gains on transfer of VDA

For computation of gains on transfer/ sale of a VDA, the cost of acquisition of such asset must be deducted from its sale price.

|

Particulars |

Amount |

|

Full value of consideration |

XXX |

|

Less: Cost of Acquisition |

(XXX) |

|

Taxable gains on transfer of VDA |

XXX |

Deductions available in computation of gains from VDA

The law does not allow any other form of deduction except the cost of acquisition of such VDA for computation of gains arising out of the transfer.[3]

Availability of Indexation benefit on transfer of VDA

The law has categorically denied any benefits of indexation or cost of improvement with respect to computation of gains on the sale/ transfer of VDA.

Allowability of Set-off of Loss on VDA

In a scenario of occurrence of loss on the transfer/ sale of virtual assets, such loss cannot be set off against:

- Gain arising on the transfer of another VDA.

- Income under any other head of income.

A simple example for the same would be as follows:

Person “A” sells VDA “X” and makes a profit of Rs.60,000 in one transaction and in another transaction incurs a loss of Rs.1,00,000 on sale of VDA “Y”.

In this case, he/she will be liable to pay tax on the profit made of Rs.60,000, but the loss that he/she has suffered, would not be set off against the profit made, even though the transactions may have been simultaneously done and falling under the same head of income.

Allowability of carry forward of losses on VDA

The loss arising on VDA cannot be carried forward. This development is interesting to note as all other asset classes have the benefit of setting off losses and carrying forward of those losses into the next year, making this particular asset class the least investment friendly.

Rate of Tax on gain on transfer of VDA

The gain on the transfer of VDA is to be taxed at a flat rate of 30%, plus cess and surcharge[4].

Applicability of Tax Deduction at Source (“TDS”) provisions in case of VDA

Section 194S was inserted vide Finance Act, 2022 for withholding of tax on transfer of VDA. The details are as follows:

When to deduct tax at source?

TDS must be deducted at earliest of:

- making payment (by any mode); or

- crediting of such sum to the account of the resident

Threshold for TDS

The person making payment would be liable to deduct tax under following circumstances:

|

Person making payment (Deductor) |

Consideration |

|

Individual or HUF, not having any Profit/Gain from business or profession |

Exceeds Rs.50,000 in a FY |

|

Individual or HUF: -having Income under head 'Profit/Gain from business or Profession' and; -turnover from business does not exceed Rs. 1 Crore or; -receipt from profession does not exceed Rs. 50 Lacs in the FY preceding the FY in which VDA is transferred |

Exceeds Rs.50,000 in a FY |

|

Other cases |

Exceeds Rs.10,000 in a FY |

Whether TDS applicable in case of recipient being Non-Resident?

TDS u/s 194S is to be deducted by any person making payment to a resident person. Hence, no TDS to be deducted u/s 194S if the Recipient is a Non-Resident. However, the provision of Section 195 would get attracted in such cases.

Rate of TDS

TDS must be done at the rate of 1% of the total consideration (excluding GST, if any).

Valuation of consideration for the purpose of deduction of tax on transfer of VDA

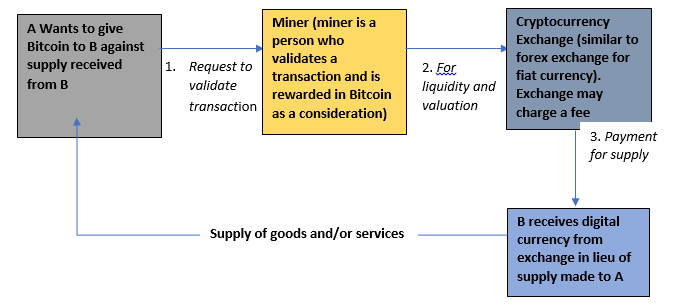

The transfer of VDA can take place either:

- Through Exchange

- Through Peer-to-Peer

Valuation of consideration under the following circumstances is discussed below:

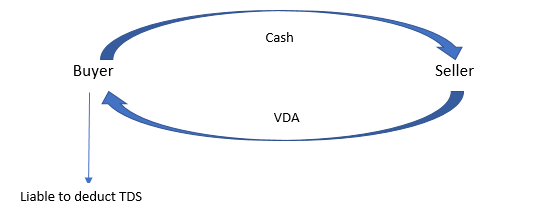

A. Liability to deduct tax when the consideration is in Cash

1) Transfer on Peer-to-Peer:

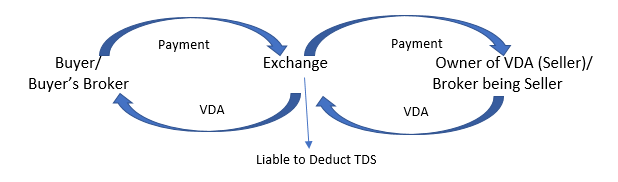

2) Transfer through Exchange:

Value of consideration will be Actual Amount Paid/Credited by buyer (deductor). Further, liability to deduct TDS when the consideration is in Cash under different scenarios, is discussed below:

a. Exchange making payment/crediting amount to seller/broker being the seller [i.e. broker is owner of the VDA]: Exchange is liable to deduct tax under section 194S.

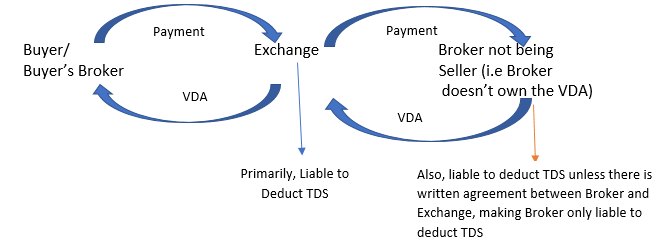

b. Exchange making payment/crediting amount, but broker involved in transfer is not the Seller: Both, the Exchange and the Broker will be liable to deduct TDS, unless there is a written agreement between Exchange and Broker, making only the Broker liable to deduct tax.

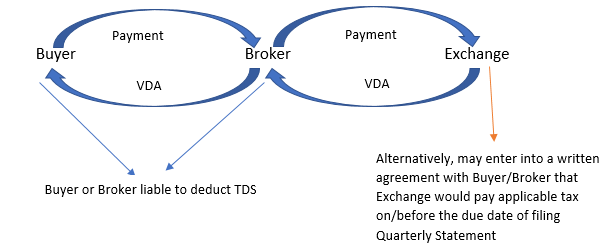

c. VDA owned by and transferred through Exchange

Primarily, Buyer/Broker being the person making payment would be liable to deduct TDS. However, upon a written agreement between Exchange and Buyer/Broker, the Exchange may itself deposit the amount of tax and file quarterly statement in Form 26QF

“Exchange” means any person that operates an application or platform for transferring of VDAs, which matches buy and sell trades and executes the same on its application or platform.

“Broker” means any person that operates an application or platform for transferring of VDAs and holds brokerage account/accounts with an Exchange for execution of such trades.

B. Liability to deduct tax when the consideration is in kind, wholly or partly, or in exchange of another VDA and cash is not sufficient to meet TDS liability

Person making payment should ensure that the required tax on such consideration is deposited, before releasing the consideration.

1) VDA against VDA under Peer-to-Peer:

Under Peer-to-Peer transaction of VDA against VDA, both the parties are buyer as well as seller, hence both parties are liable to ensure that the tax is deposited by another before release of consideration.

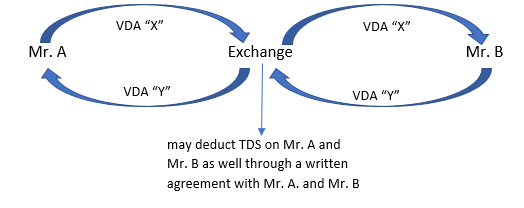

2) Transfer of VDA against another VDA through Exchange:

In case the transaction of transfer of one VDA against another VDA is through Exchange, for the sake of convenience, the Exchange may opt to deduct and pay the tax on the Buyer as well as the Seller. This can be done by the Exchange through an agreement with Seller/Buyer.

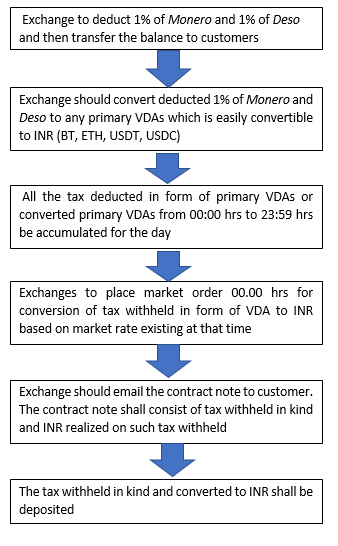

Valuation of TDS deducted in ‘Kind’ under transaction of VDA against VDA:

If the Exchange opts for tax deduction, the possibility of tax deduction in kind may arise and hence the need for its conversion to cash before deposit with Government may arise.

To this the CBDT has specified following mechanism:

Illustration:

VDA Monero is traded against the VDA Deso (both not being primary VDAs) through the Exchange. And the tax @ 1% of Monero and Deso is deducted by the Exchange in kind.

Special Case: Transaction where Payment is made through Payment gateway.

Payment gateway would NOT be required to deduct tax if person required to deduct tax (as discussed above) has deducted the tax. For implementation of this, payment gateway may take an undertaking from the person responsible to deduct tax in this regard.

Effective date of Section 194S: 01st July 2022

How the threshold limit of Rs. 50,000 or Rs. 10,000 is to be calculated?

- CBDT has clarified[5] that the consideration threshold limit of Rs. 50,000/Rs. 10,000, is to be counted from 01 April 2022.

Hence, if the threshold limit of Rs.50,000/Rs.10,000 is exceeded by 30.06.2022, TDS is to be deducted on all the payments/credits made on/after 01.07.2022.

Summary Views:

The framing of tax law to curb tax leak on the gains arising from a VDA is a valiant step. The CBDT has vide introduction of the tax provisions on VDA and the subsequent notifications, tried to address the several issues on taxing of VDA transactions. However, the concept of trading in VDA is yet globally evolving and with passage of time certain practical difficulties are likely to arise, necessitating further clarifications and guidance by CBDT vis-à-vis taxation of VDAs. This would have to be done transparently, on a dynamic and pro-active basis.

Under the current laws, in situations where the buyer and the seller are both residents, are unknown to each other and are trading through an Exchange operating outside India, would require further analysis on who shall be liable to deduct the TDS. Forgoing this, how these transactions will be identified and who would be the reporting entity, would remain an important question that would need to be addressed.

[1] On 7th October 2022 RBI has announced that limited pilot launches of Central Bank Digital Currency [CBDC] or Digital Rupee (e₹) will begin soon

[2] Notification No. 74/2022/F. No. 370142/29/2022-TPL (Part-I)] dated 30th June 2022

[3] Cost of mining is not considered under “cost of acquisition”.

Mining: Validation of cryptocurrency's coins under Blockchain transaction

[4] Cess rate is 4% and Surcharge is as follows:

- For Individuals

|

Income range |

Rs. 50 Lakhs to Rs. 1 Crore |

Rs. 1 Crore to Rs. 2 Crores |

Rs. 2 Crores to Rs. 5 Crores |

Exceeding Rs. 5 crores |

|

Rate |

10% |

15% |

25% |

37% |

- For Domestic Company

|

Income range |

Rs. 1 Crore to Rs. 10 Crores |

Exceeding Rs. 10 crores |

|

Rate |

7% |

12% |

- For Foreign Company

|

Income range |

Rs. 1 Crore to Rs. 10 Crores |

Exceeding Rs. 10 crores |

|

Rate |

2% |

5% |

- For Partnership firm, LLP, Local Authority and Co-operative society @ 12% on Income exceeding Rs. 1 Crore.

[5] Circular No. 13 of 2022/F. No. 370142/29/2022-TPL (Part-I) dated 22-06-2022

Game of GST – Winter is Coming

This article has been co-authored by Palak Goyal (Manager, TMSL).

The second biggest market for online gaming industry is astonished by the DGGI issuing a SCN of a whooping INR 21,000 crore alleging non-payment of GST. India, only second to China has more than 400 gaming companies and caters to more than 420 million online gamers. This incredible rush in the number of gamers is driven by the average age in the country, higher disposable income and easy and cheap access to smartphones and internet. However, the surge is not yet over; according to a study, the Indian gaming industry is set to soar to 5 billion dollars by 2025!

With these facts, it did not come as a surprise when our Hon’ble Finance Minister stated animation, visual effects, gaming, and comics sector (AVGC) as one of the sectors to focus upon and hence a task force was formed for the same. However, recently when the DGGI slammed one of the unicorns in gaming industry with an INR 21,000 crore notice, it sent a shock wave in the country. Being one of the biggest SCN ever issued in the GST regime, there is much hype about the matter.

Background

The assessee in this case had been issued an intimation in Form DRC-01A dated 8 September 2022 alleging non payment of GST @ 28% on the activity of the assessee. The assessee subsequently filed a writ before the Karnataka High Court demanding an interim stay on the intimation and a to stop the revenue from acting upon the same. The petitioner relied upon the following submissions to obtain an interim stay:

- The petitioner is engaged in hosting skill based online games on its platform as an intermediary.

- Rummy, constitutes more than 96% of games played on petitioner’s platform. Various courts including the Apex Court have time and again held that rummy is a game of skill and not a game of chance.

- The petitioner is a bona fide taxpayer as it has deposited INR 1500 crores tax (income tax and GST) till 30 June 2022.

- The intimation is wrong in law as it alleges that the petitioner is involved in the supply of an actionable claim which is not the case. The only actionable claim was between the players and the petitioner did not have any claim or beneficial interest.

- The intimation invokes Rule 31A of the CGST Rules 2017, the validity of which is seized and sub-judice before the division bench of this court.

- The notice suffers from lack of jurisdiction since its not been issued by proper officer. The same is also vitiated with malice. It is also arbitrary and violative of Article 14,19 and 21 of the Constitution of India.

- The petitioner has earned a little over INR 4000 crores during the period June 2017 to June 2022. However, the notice has been issued for the same period for INR 21,000 crores. If the demand is enforced, it will cause irreparable damage and hardships to the petitioner.

- The GST Council has not yet taken any decision on taxability of online gaming sector; hence, the intimation is contrary to the same.

The revenue on the other hand contested the petition on the grounds that a petition cannot be maintained against an intimation only, which is only an option for the petitioner to exercise payment of tax, interest and penalty (15%). Therefore, the said petition is liable to be dismissed. Also, merely because the GST council has not taken any decision, the petitioner cannot rely upon the same.

However, the Karnataka HC stated that the issue at hand is a culmination of contentious issues and disputed questions which will have to be decided at the time of final disposal of petition. Hence, the HC granted an interim stay against the intimation issued.

Nonetheless, the department issued a SCN to the assessee on 23 September 2022. The issuance of SCN could have been made due to the time barring limitation of period specifically for demand pertaining to FY 2017-18 . Pursuant to such issuance of SCN, the Karnataka HC commenced the hearing on 27 September wherein the petitioner stated that considering the entire value of online gaming industry in India is INR 14,000 crores, a demand of INR 21,000 crores on petitioner alone is absurd! Moreover, the petitioner in the apprehensions of attachments and arrests, sought a stay on the SCN till the time the hearing commences post Dussehra break.

How the industry works and GST implications

Online gaming industry has several streams of revenue. The key ones are:

- The gaming platform charges ‘rake fees or enrollment fees to the players for usage of online gaming platform. In such cases, the platform may or may not allow gaming through monetary methods.

- In case players play games with monetary amounts, there is generally a prize money pool which is nothing but a pool of all monetary contributions. This prize money is later on released to the winner of the game after deducting a commission of the platform. However, in case of non-monetary games, only rake fee is charged from players for facilitating the game.

- The gaming platform or app does not charge any rake fees to the player. However, the player may have to pay for any additional features such as unlocking the next level, buying extra life, performance boosters etc.

Apart from the above revenues, a gaming platform also derives significant advertising revenue from in-app advertisements. From the GST perspective, the possible treatment of such revenues is given below (which may differ basis the facts of each case):

- Rake fees or enrollment fees – May be subject to GST

- Prize money pool or contest fee – The pool created by collecting money from all players may not be subject to GST provided that the same is refunded to the winner. Any deductions whether in the form of commission or otherwise may attract GST.

- Additional charges for unlocking other features on the app – GST may be applicable on such revenues.

- Advertising revenues – GST may be applicable on such revenue.

However, the industry is currently not levying GST on money deposited by players with the platform in the form of a wallet and contribution to prize pool as the same is considered to be in the nature of actionable claims which are excluded from the definition of ‘supply’. Moreover, no GST is currently being paid on prize money distributed by gaming companies to winners as the same is considered as ‘transaction in money’. Thus, the only revenue which is offered to GST is platform fee.

The pertinent question and the bone of contention here is whether GST should be levied on the entire prize pool money/ contest fee or only earnings derived from it by the gaming platform which is commonly termed as Gross Gaming Revenue (GGR). Another question is whether the gaming platform is engaged in hosting games of skill or games of chance; depending on the classification, the rate of tax would be determined – whether 18% or 28%!

These two questions have more or less given sleepless nights to the entire gaming industry. Their only ray of hope was the Group of Ministers (GoM) who have been entrusted with the responsibility of clarifying the taxability on the online gaming sector. However, this GoM in July 2022, suggested that a flat rate of GST @ 28% should be levied on the entire consideration, whether they are games of skills or games of chance. This suggestion sent the industry in a pandemonium, thus forcing the GoM to rethink their report and suggestions. While we await the GoM to pronounce their verdict and GST council to agree on such verdict, the industry is receiving intimations and notices.

In the notice at hand, the SCN has alleged that the assessee has collected a contest money of INR 77,000 crores and has levied tax @ 28% on the same. The assessee has defended its ground on the premise that it only retains a platform fee and has already discharged GST @ 18% on such fees. The question here is that if the assessee has distributed the entire contest money barring its platform fees, there remains no revenue to levy tax on. However, the assessee must be able to substantiate the amount distributed to the winners. Another point to ponder here is that the assessee has stated in the petition that 96% of its platform is used for rummy which is a game of skill. However, the remaining 4% of INR 77,000 crores which amounts to INR 3,080 crores is also not an insignificant sum.

One can also draw parallels from the Cryptocurrency industry. Whether GST should be levied only on the exchange fees of crypto platforms or on the entire traded value – is a question which is haunting the crypto industry as well. However, a distinction can be drawn from the horse racing industry as one could interpret horse racing as a game of chance or betting or gambling as against online games which mostly are games of skill.

Conclusion

A good start to scatter the clouds of ambiguity would be to frame accounting standards specific to online gaming sector, in lines with global best practices. Once accounting standards are in place, determining taxability becomes much simpler. Moreover, if one was to refer to global practices, most countries levy tax on platform fees or GGR earned by gaming companies. These include UK, Sweden, Germany, Denmark etc.

Possible next steps for the Industry and the Government

- Frame Accounting policies or standards in association with professional bodies to understand the long-term impact on the sector

- Give due consideration to global best practices

- Deliberate and frame the taxation rules - Direct tax and Indirect tax both. It would be vital to have certain members from the industry onboarded for such deliberation to consider both sides of the coin

- Roll out these policies at the earliest to avoid any undue litigations and disputes

- From an industry perspective, strong representations need to be made to the policy makers and for companies which have yet not become a part of these representations, may wish to have themselves onboarded.

Nonetheless, multiple trade bodies and professional firms have highlighted that levying GST on the contest money would send the industry in spiral. The industry has been contributing significantly to the tax treasury of the country. An optimum tax structure could increase these collections and make the sector soar high also supporting the AVGC vision of the hon’ble Finance Minister. However, the opposite could mark the end of a reign of online gaming sector in India, as there will only be a handful companies which would be able to survive this tax regime.

[The views are personal.]

“Non-Fungible Tokens and GST”

An abundance of digital financial assets (as termed by the OECD) or Virtual Digital Assets as defined under the Income Tax Act, 1961 have flooded the markets, from crypto currencies to NFT’s and tokenised forms of real-world assets like gold and other commodities. While the true nature of these new age financial instruments has everyone scratching their heads, NFT’s have captured the imagination of the world.

While the Silent Generation collected paintings and art work, Generation X collected marbles, trading cards, cigarette wrappers, etc. The Millennials; Generation Z are focused on 21st century digital collectables and NFT’s with digital scarcity as a selling point. Powered by the blockchain technology and existing completely in the digital space, NFTs in essence are lines of computer code, that manifests as a digital representation of some other data, i.e. (metadata – data that references other data).

The Supreme Court in the case of Tata Consultancy Service Vs. State of Andhra Pradesh[1] had held that the term ‘goods’ as used in Article 366(12) of the Constitution of India and as defined under the said Act are very wide and include all type of movable property whether the properties be tangible or intangible. Even intellectual property, once it is put on to a media whether it be in the form of books or canvas (in case of painting) or computer disc or cassettes and marketed would become goods. As in the case of painting or books or music or films, the buyer is purchasing the intellectual property and not the media that is paper or cassette or disc or CD. The term "all materials, articles and commodities" includes both tangible and intangible/incorporeal property which is capable of abstraction, consumption and use and which can be transmitted, transferred, delivered, stored, possessed etc. The software programmes have all these attributes. Goods include all material, commodities and articles. Commodity is an expression of wide connotation and includes every thing of use or value which can be an object of trade or commerce.

Whether NFTs would qualify as goods in the light of the test laid down by the Supreme Court in TCS case is an interesting question by itself. The Finance Act, 2022 amended Section 56 of the Income Tax Act, 1961 to recognize Virtual Digital Assets (VDA) as ‘property’.

Spanish Tax Ruling

The Spanish Tax Authorities in a recent ruling in Binding ruling V0482-22, of March 10, 2022, issued by the Spanish General Directorate of Taxes discussed the nature and taxability of NFTs. In the case, from an analysis of the Spanish VAT provisions, it was inferred that the ‘any natural or legal person would be carrying out an economic activity when it orders for its own account material and human resources of production, with the purpose of intervening in the production and/or distribution of goods or services. In such a case, and, if carried out independently, the person should be considered, as a general rule, a taxable person for VAT.’

Further, while discussing the nature of NFTs either as a good or a service, the Tax Authorities drew the conclusion that in the cases where NFTs are not representatives of real-life goods (which is mostly the case), NFTs then take the nature of digital certificates of authenticity associated with a single digital file. Therefore, the NFTs act as unique digital assets that cannot be exchanged with each other. In accordance to the Spanish VAT legislations, the Authorities made the ruling that in light of the above finding it would not be appropriate to deem NFTs to be goods and their trade a supply of goods where the NFTs do not correspond to a right for their holder to be entitled to some underlying tangible goods. As per their finding therefore, the object of supply is the digital signature without any other underlying supply. Once the inference that NFTs are not goods was made, the Spanish Tax Authorities also made one particular finding that proves relevant when measured against our GST laws. In the operative part of the ruling, the Authorities also made a finding that NFTs are electronically supplied services which are services that, by their nature, are mainly automated and require minimal human intervention and are not feasible without information technology.

This categorization of NFTs by the Spanish Tax Authorities when compared with Indian GST provisions would require the examination of OIDAR services defined in terms of Section 2(17) of the IGST Act. Clause (ii) covers provision of e-books, movie, music, software and other intangibles through telecommunication networks or internet. Therefore, another perspective would be whether NFTs would qualify as ‘other intangible’ and thus fall under OIDAR services.

In the context of income tax, all NFTs are not considered as virtual digital assets. In terms of Explanation (a) to Section 2(47A) of the Income Tax Act only notified NFTs shall be considered as virtual digital assets for the purpose of income tax.

German Court

Recently, the Federal Finance Court of Germany in the case of Bundesfinanzhof, BFH has held that mere participation in a game and ‘in game sales’ which shapes the gaming experience in interaction with other game participants does not constitute participation in real economic life. Thus, renting of ‘virtual land’ in a game was not considered to be a service liable to VAT. However, when the in-game currency is exchanged against real fiat money the same is taxable.

Five dimensions

In the GST scenario no amendments have been made in the statute in the context of crypto currencies or crypto assets. Whether NFTs would constitute good or service can always be the subject of debate. In fact, debate currently exists even with reference to intellectual property rights and the general view is that transfer of intellectual property rights would amount a supply of goods while licensing of intellectual property rights would fall within the domain of service. There are five dimensions to the exercise of examining GST applicability on a sale of NFT.

Assuming, there is an NFT created and owned by a celebrity who is a resident of another country without any place or establishment in India and the said NFT is purchased by an individual in India, the first dimension is that, if the transaction is considered as a supply of goods, there is no point of import or physical import for levy of customs duty or IGST. The second dimension is that, where the transaction is considered as a supply of service and falls within the scope of OIDAR services, the recipient would be a ‘non-taxable online recipient’ and the liability to pay GST would be on the foreign supplier. Enforceability and implementation would be an issue.

The third dimension to the issue is the aspect of consideration. Assuming, the individual in India has a wallet in which cryptocurrency purchased by him is loaded and the said cryptocurrency is used to purchase the NFT, whether cryptocurrency can be considered as consideration or not can be a matter of debate. The definition of ‘consideration’ includes payment whether in money or otherwise. Given the fact that cryptocurrency is yet to be recognized as legal tender, it will not qualify as ‘money’. Whether it can fit into ‘otherwise’ is another open question.

The fourth dimension is whether NFT constitutes consideration for the transfer of cryptocurrency or whether the exchange of cryptocurrency for NFT constitutes a barter transaction.

The fifth dimension to the issue is jurisdiction. The blockchain would exist in the internet and thus could be anywhere. The wallet could exist anywhere. Tracking of such transactions for the purpose of examination of GST applicability can be a humongous task. If the decision of the German Court is applied transactions that take place in the virtual world using virtual currencies may even be outside the ambit of the GST in the real world.

Given the various ramifications and the complexities in the existing statutory framework, taxation of transactions involving crypto assets such as NFTs in the GST regime is not going to be easy. The law may have to be amended to provide for a simpler system. However, it would still be a huge challenge to track transactions unless the nature or price involved in the transaction attracts media attention.

[1] (2004) (SC)

Taxation in the World of Metaverse

The World of Metaverse:

Nowadays, Metaverse is a trending topic to discuss on, Metaverse is the most promising advancement of technology in the world of digitalization.

The metaverse is a decentralized platform based on blockchain technology that enables users to create their own virtual worlds. Metaverse is a digital/virtual universe based on technology, where human beings can digitally be present at anywhere in the world and do anything which could either be possible in real life, they can purchase, roam, interact with others, and engage in a wide range of activities, including shopping, banking, and social networking, experience the place which may be far apart from him in person. This technology is basically based on Web 3.0 application, which may revolutionize the world.

As, the demand of Internet and its accessibility has been increased drastically in the couple of years, where, Latest figures show that an estimated 4.9 billion people are using the Internet in 2021, or roughly 63 per cent of the world’s population. This is an increase of almost 17 per cent since 2019, with almost 800 million people estimated to have come online during that period[1]. Being shopping online, or surfing online, the data of the target consumers can also easily be traced by companies for better analysis and strategic planning to increase its turnover. Thus, the Companies are spending billions of dollars on the digital world to give more satisfactory and user-friendly experience to its customer during the screen time. So, as the case with Metaverse.

In the age of Digitalization, many companies are in the process of listing themselves on the metaverse and many had already listed themselves on the world of Metaverse. Following are the few companies, listed on the metaverse. Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Amazon, Nykaa, Apple, Epic Games, Roblex Corporation, Nike, Decentraland, etc[2]. Moreover, Banks are also getting Listed on the Metaverse, The Standard Chartered Bank, recently became the largest major bank to embrace the technology of metaverse[3].

Nike recently launched its 20,000 Sneakers as it’s a part of Nick Dunk Genesis Cryptokicks on Metaverse as NFTs out of which 98 were scare items making it more valuable and someone paid $130,000[4] for those sneakers. It’s an economical fact that scares the resources higher the price would be.

Singer Daler Mehndi, is the first Indian Singer to purchase the Land on Metaverse, named as “Balle Balle Land” to host films and concerts over the VR technology which will sell the merchandise as NFTs over Blockchain technology[5].

Similarly, as in the actual world, payments in the metaverse can be made in an assortment of ways. As organizations and people rush to the metaverse, new payment systems are being created to oblige the necessities of this developing local area. The most well-known technique for payment is made by means of blockchain-based computerized monetary standards, which can be utilized to buy labor and products from vendors inside the metaverse. One of the critical advantages of computerized cash payments in the metaverse is that they are borderless. This implies that clients can send and get installments from anyplace on the planet without stressing over exchange rates. While the advanced adaptation of blockchain technology, the cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) may be used as payment strategies in the metaverse.

The Land on the Metaverse can be purchased through Cryptocurrency, especially in Ethereum. You will also need to have virtual wallets that can store NFTs like Metamask or Binance. Once you buy a land, the sale and ownership of the land are recorded via the transfer of NFTs. The transfer will take a few seconds as it will verify if your digital wallet has enough currency to buy the said land, after that it will be conveyed that you now own the land legally[6]. The Land on the Metaverse shall be measured in tiles, which will be unique from any other tile in the metaverse, making it Non-Fungible. (Non-Fungible means, Unique, which cannot be replaced with something else).

Taxation Aspect:

In the Metaverse, NFTs are to be sold on the Blockchain technology and through Cryptocurrencies.

According to the Section 2(47A) of the Income Tax Act, 1961,

“Virtual Digital Asset” means

(b) a non-fungible token or any other token of similar nature, by whatever name called;

Explanation- For the purpose of this clause:

- “non-fungible token” means such digital asset as the Central Government may, by notification in the official Gazette, specify;

As per the ITA, only those NFTs shall be taxed which are notified by the Government. As of now, no NFTs has been notified.

As and when Government notifies any NFT under this section, the laws of Section 2(47A) shall be applicable and those NFTs shall be considered as Virtual Digital Assets. But, for this article, let us assume that Government has notified the NFTs (See point 2 below).

There are few methods which may be followed to earn income from the Metaverse, which may be as follows, 1) Renting of Land, 2) Sale of Land, 3) Running the Business, 4) Hosting an event, etc.

Let us see, how these transactions be taxed under the current Income Tax Act, 1961.

- Renting of Land:

According to the ITA, rental income shall be taxed under the head “Income from House Property”, whereas the charging section of IHP, say that the income should be earned from the house property and the land appurtenant thereto, in the case of metaverse, there is no house property or the land appurtenant thereto, therefore the income earned from letting out of Virtual Land in Metaverse, cannot be taxed under the Head House Property.

The Rental Income shall be taxed under the Head “Profits and Gains from Business and Profession” (PGBP) or “Income from Other Sources” as applicable on the case.

- Sale of Land:

As, discussed above, Land is the NFT, and the transfer of NFT shall invoke Section 115BBH(1) of the ITA:

“Where the total income of an assessee includes any income from the transfer of any virtual digital asset, notwithstanding anything contained in any other provision of this Act, the income-tax payable shall be aggregate of-

- The amount of income tax calculated on the income from transfer of such Virtual Digital Asset at the rate of thirty percent; and……”

As per Section 115BBH(1), the income arising from the transfer of VDAs shall be taxed at 30% plus surcharge and cess. Such income shall be computed without deduction of any expenditure, except the cost of acquisition of the VDAs, if any. Further, loss arising from the transfer of a virtual land shall not be allowed to get set-off against any other income, whether from VDA or not.

- Running the Business:

Any income earned from running of business on metaverse shall be taxed in the same manner as any other business income is taxed in ordinary course. All the expenses relating to business shall be claimed, and other deductions can also be availed by the assessee. There is no specific treatment for the business operated under metaverse.

TDS Requirement u/s 194S (effective from 01 July 2022):

Section 194S to the Act, which would provide for a 1% tax deduction on payments made for the transfer of a virtual digital asset to a resident. However, no deduction will be required if the consideration paid during the financial year does not exceed ₹50,000/- (in the case of a specified person) or ₹10,000/- (in the case of a non-specified person) in any other case.

For the purposes of section 194S, a Specified Person is defined as

An individual or a HUF whose total sales/gross receipts in the fiscal year immediately preceding the fiscal year in which such virtual digital asset is transferred do not exceed ₹1 crore (in the case of a business) or ₹50 lacs (in the case of a profession). And an individual or HUF who receives no income under the heading “Profit and gains of business or profession.”

When the consideration is entirely in kind or in exchange for another virtual digital asset, there is no part in cash; or when the consideration is partly in cash and partly in kind, but the cash portion is insufficient to meet the liability for a tax deduction in respect of the entire transfer, the person paying such consideration must ensure that the tax has been paid before releasing such consideration.

Payments made by a individual will be exempt from the provisions of Sections 203A and 206AB. And the section further states that once the tax has been deducted under section 194S, no other TDS/TCS provision applies to the transaction. Where tax is deductible under both section 194-O and proposed section 194S, tax is deducted using section 194S rather than section 194-O.

Concluding Remark:

The metaverse is still in its beginning phases of improvement, yet it is rapidly turning into a well-known objective for web-based shopping. As blockchain innovation and the metaverse keep on advancing, we can hope to see an expansion of payment techniques accessible for dealers and purchasers to browse. Shoppers can exploit the developing interest in the metaverse by tolerating digital forms of money and NFTs, depending upon the labor and products being advertised.

[1] https://www.digitaljournal.com/pr/a-guide-to-payments-in-the-metaverse#ixzz7SVNQfRXF

[2] https://www.analyticsinsight.net/top-10-companies-working-on-metaverse-and-its-developments-in-2022/

[3]https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/cryptocurrency/blockchain/standard-chartered-bank-becomes-the-latest-major-bank-to-enter-metaverse/articleshow/91251878.cms

[4] https://www.cnet.com/personal-finance/crypto/these-nike-nft-cryptokicks-sneakers-sold-for-130k/

[5]https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/wealth/tax/how-will-income-from-land-in-metaverse-be-taxed/articleshow/91332851.cms

[6]https://www.bgr.in/how-to/how-to-buy-land-sandbox-digital-wallet-crypto-metaverse-decentraland-1251087/#:~:text=You%20can%20buy%20a%20plot,a%20purchase%20in%20the%20metaverse.

Decrypting the Crypto Tax

Crypto currency has been the buzz word over the last couple of years. Even though the same has been in existence for quite long, never before were they in limelight among all the stakeholders. The response in the international arena towards cryptos has been widely different. On the one side, we have China which has banned cryptos entirely and the other hand we have various states in Switzerland accepting tax payments in cryptos. The IMF has also cautioned about the impact of cryptos on the monetary policy and has advised Elsalvador to reverse its decision to accept Bitcoin as legal tender. India had perfect thriller script in the case of cryptos as well. The RBI first banned the cryptocurrencies which was overturned by the Honourable Supreme Court, later, the Government was set to introduce a bill banning mining of cryptocurrencies in India which was not tabled in the Parliament. Further, there were different views that Government would not go for complete ban on cryptocurrency and that it would only restrict its usage only as an investment asset.

Amidst this chaos on the policy stand point, cryptocurrency has attracted quite a large number of investors in India without class discrimination where both the HNIs and the lower middle class population has invested aggressively in cryptos. The digital asset arena is not limited only to cryptocurrencies but others such as NFTs and Metaverse which have already been stated as the next big revolution which would transform the future landscape.

NFTs

The other technological advancement based on the block chain technology, which is gaining traction is NFTs (Non Fungible Tokens). There are multiple types of assets based on NFTs. The prominent among them would be digital assets (copyrighted photographs, art, music album, video etc) of prominent sportspersons, Bollywood stars etc., the ownership in which is being distributed with the help of transferable NFTs issued to the subscribers. The other prominent type of NFTs are the shares (tokens) in the virtual companies. In USA, Decentralized Autonomous Organisation (DAO) also works on block chain technology based smart contracts and issues token (shares) to members. Other countries are yet to catch up with this. But though the tokens are in the nature of shares, they are nevertheless NFTs.

Metaverse:

With gaining traction in cryptocurrencies and NFTs, the spotlight has also turned on the new virtual reality and digital life “Metaverse”. Metaverse is a virtual world where you can connect with people via your digital avatars. A digital avatar is a close replica of a real human being. In the recent past, accomplished MNEs have shown keen interest and have started revolutionizing into the new era. Recently, Microsoft cited metaverse as a reason for acquiring the game developer Activision Blizzard for $68.7 billion, saying the deal would provide “building blocks for the metaverse.” Facebook’s founder, Mark Zuckerberg, has also bet on the metaverse and renamed his social networking company Meta. Few other game development companies like Roblox, Epic Games, Tencent are focusing on building a metaverse platform where people can talk to each other, talk to brands and can even stay in the virtual world for more. The top footwear brand Nike has built its virtual world “Nikeland” in collaboration with Roblox, wherein, players will get a chance to try new sports shoes and run marathons in Nikeland.

The India Story:

Industry estimates suggest there are 15 million to 20 million crypto investors in India, with total crypto holdings of around 400 billion rupees ($5.37 billion). No official data is available on the size of the Indian crypto market. However, as per Triple A (a business enabler of cryptocurrency solutions headquartered at Singapore), it is estimated that over 100 million people, 7.30% of India’s total population, currently own cryptocurrency as of 2021. According to a report by cryptocurrency research firm Chainalysis, India is one of the world's fastest growing crypto markets, increasing by 641% between July 2020 and June 2021.

There are many crypto exchanges in India such as CoinDCX, Zebpay, WazirX, CoinSwitch Kuber, Unocoin and Bitbns. Leading cryptocurrency exchange, WazirX, witnessed record trading volume of over $43 billion in 2021 – the highest in India – a growth of 1,735% from 2020. BitBns, another leading exchange, increased its user base by 849% and trading volumes by more than 45 times in the last year.

On the NFTs front, the volume of NFTs that are traded in the market has increased by 43% from April 2021 to June 2021. According to Reuters, the proportion of NFT sales during the first 6 months of 2021 grew to $2.5 billion.

As per BitsCrunch, a blockchain analytics firm, India contributes around 5% of the global NFT space. The firm also added that determining the exact number is difficult as a lot of buyers use pseudonyms through decentralised exchanges.

It has been evident that India’s top IT services firms are working on embedding various technologies to tap the Metaverse market, which is estimated to provide a $8 trillion opportunity, as per global investment bank Goldman Sachs. Further, few other start-ups as well have explored avatar-based immersive platforms that enables virtual conferencing and networking in a 3D environment.

More than 500,000 Indian users have shown their interest in NFTs and metaverse projects from the beginning of November 2021, according to a report by DappRadar, a company that tracks user behaviour across blockchain projects.

India has been ranked fifth only behind the US, Indonesia, Japan and the Philippines in terms of interest in metaverse projects, according to the report that was published on 24 November, 2021.

Taxing the fad:

The increasing interest of Indians in the crypto space and the persisting uncertainty on its legal framework, called forth the ambiguity on taxation of the gain on cryptos with divergent views that the gains should be taxed either as income from business or profession or capital gains.

An Inter-Ministerial Board constituted in 2017 to study the issues related to virtual currency, laid forward its report along with a draft Bill in 2019. The report highlighted that, large fluctuations in price preclude cryptocurrencies from being a suitable store of value and that they lack intrinsic value. It was set forth clearly that the lack of Sovereign backing prevents crypt currencies from being a legal tender, and therefore have no inherent value beyond the utility their underlying technologies represent. In this back drop, the pendulum was tilting towards categorising the investments as speculative in nature rather an investment for appreciation of value.

The Government in the Union Budget 2022 has provided much needed direction on the taxability of cryptocurrency and other digital assets. The Finance Bill 2022 proposes to tax the income from the transfer of virtual digital assets at the rate of 30% without any recourse to setoff of loss either from the same source or other sources of income and the carry forward of loss is also prohibited. More importantly only the cost of acquisition of the asset is allowed as deduction and no other expenditure shall be allowed to be claimed while computing the income from the transfer of virtual digital asset. This approach clearly indicates that the Government intends to discourage the investments in virtual digital assets especially the cryptocurrencies. This is understandable considering the fact that there is no law at present to regulate the crytpo currencies and the extent of risk involved is also not clear. The estimate on the number of people investing in these cryptos varies drastically from source to source. It’s a welcome move that the Government proposes to bring its own digital currency based on the same technology, showing inclination towards adopting the technology which promises to be a solution for various issues being faced currently.

NFTs has had its share of success in various instances across the globe. One such is that the technology could help in protecting the copyrighted assets from piracy. India faces huge financial loss due to piracy and the Government also losses tax revenue by virtue of it. The Government should quickly bring in a law to regulate the NFTs and encourage its use and remove it from the 30% tax bracket. Though the Act uses the term NFTs, it has not been defined and has provided the Board the right to include various assets under this list and along with power to notify the NFTs which would be excluded from the 30% tax bracket. New withholding tax regime has also been introduced for the transfer of virtual digital assets with onus being on the person responsible for the payment of consideration to deduct tax @ 1% on payment of consideration of over and above Rs.10,000 in a year in general and in specific cases for Rs.50,000 and above. As in the case of many a tax regulations, there are certain ambiguities even in the case of the taxation of virtual digital assets such as the follwing :

- The definition of Virtual Digital Assets is very broad and might end up covering within its ambit the reward points, flexi points etc which is offered by various companies to its customers

- The responsibility to deduct TDS is on the person responsible for payment. In the case of cryptocurrencies where the transaction happens through crypto exchanges, whether the person responsible for payment would be the actual seller or the exchange through which the payment is routed

- In the cases where the payment of consideration is through crypto assets, the person responsible for payment shall ensure that the tax on the transaction is paid. No proper mechanism has been prescribed for the same, which could create lot of ambiguity on the part of the person responsible for making the payment.

- The amendments are effective from the FY 2022-23 but as stated earlier, numerous transaction have taken place in the last couple of years, the taxability of the same would be subject to litigation. However, with proper documentation to support the claims, the litigation could be averted with income being taxed as profits and gains of business or profession or capital gains as the case may be.

Despite the above ambiguities, the introduction of a tax regime for virtual digital assets is a step in the right direction and iterations are expected considering the fact that it’s a newly evolving technology and not yet regulated. Introduction of tax regime alone shall not be construed as the government’s intention to legalise the cryptocurrency. Though the latest indications as such are that the government would permit holding of crypto currencies as assets but not as a legal tender, we have to wait and watch for the proposed regulation to be tabled in the parliament.

Crypto Tax - Everything You Need to Know

This article has been co-authored by Om Rajpurohit (Director, Corporate & International Tax, AMRG & Associates).

Introduction

The long-awaited Cryptocurrency Bill, which was supposed to be introduced in Parliament during the winter session, got delayed. Previously, the government had refused to grant cryptocurrencies the status of legal tender. In 2018, the RBI attempted to impose a ban by restricting banking services to cryptocurrency exchanges. The ban, however, was later overturned by the Supreme Court.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman proposed a crypto tax on transactions of virtual digital assets (VDA) like Bitcoin and Ethereum on February 1, 2022, while presenting the "Budget 2022". Additionally, she stated that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) will launch its own digital currency in 2022-23. The announcement has put an end to long-running speculations about how the Government of India will approach the evolving digital currency space, particularly in light of concerns raised by various sections.

The rollout of a central bank's digital currency will significantly boost the digital economy. Additionally, the digital currency will result in a more efficient and cost-effective currency management system.

What is Virtual Digital Asset?

Proposed new clause states that virtual digital asset(“VDA”) mean:

a) any information or code or number or token, generated through cryptographic means, providing a digital representation of value exchanged, with the promise or representation of having inherent value;

b) a non-fungible token;

c) any other digital asset, as notified.

Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman announced a 30% tax on income from virtual digital assets, stating that the size and frequency of such transactions necessitated the creation of a specific tax regime.

Will you have to pay tax on both gains and losses from crypto?

Crypto investors cannot set off any loss arising from the transfer of virtual digital assets and such loss will not be allowed to be carried forward to subsequent financial years.

In simple words in case any taxpayer has earned any income from the transfer of a virtual digital asset, the said income shall be subject to tax tax @ 30%. This source cannot be combined with any other source of income. If all the tranactions during the year results in positive income, the same amount shall be chargeable to tax at the rate of 30%.

No deduction in respect of any expenditure other than the cost of acquisition of a VDA shall be allowed to the taxpayer under any provision of the act.

Losses arising from the transfer of crypto assets cannot be set off against any other income and also it cannot be carried forward. However, intra-head consolidation of all VDA transactions entered during the year is permissible.

Let's look at an example to better understand this-

A taxpayer gained Rs. 5 Lakhs on the sale of Cryptocurrency A and posted a loss of Rs. 2 Lakhs on the sale of Cryptocurrency B. The taxpayer can set off the loss and the net gain from the sale of crypto assets (both Cryptocurrency A and B) and Rs. 3 lakh would be subject to tax @30%.

Will you have to pay more than 30% tax on crypto income?

The effective tax rate on income from the transfer of cryptocurrencies, NFTs, or other virtual digital assets may be higher than 30% because this flat rate excludes any applicable surcharges and cess.

The surcharge is applied at the rates of 10%, 15%, 25%, and 37% of the tax amount, depending on the taxable income, and the cess is applied at the rate of 4% of the tax and surcharge amount. As a result, gains from the transfer of Crypto assets may be subject to effective taxation at rates of 31.2 percent, 34.32 percent, 35.88 percent, 39 percent, and 42.744 percent, depending on taxable income in the case of individuals/HUFs.

TDS Implications on Virtual Digital Asset

Any person who pays consideration to a resident for the transfer of a virtual digital asset is required to withhold TDS at the rate of 1%.

There will be no TDS implication if the consideration is paid:

a) by a specified person and does not exceed INR 50,000 in the fiscal year.

b) By anyone other than the specified person, if the amount does not exceed INR 10,000 in the fiscal year.

There will be no TCS implications where TDS has been deducted.

Gift of Virtual Digital Asset

The Union Budget for 2022-23 broadens the definition of "property" to include Virtual Digital Assets, which will become effective on April 1, 2022. As a result, the gift of a Virtual Digital Asset will be taxable in the hands of the person who has received it.

Open issues

Even though this is a good beginning for the Indian crypto eco-system, certain aspects require clarification from the long-term stability perspective.

The First would be whether the acquisition cost will include direct expenses such as brokerage charges, exchange fees, and various directly incidental expenses.

There are various types of coin-like stable coins, utility coins whose value is derived from an underlying asset. Government did not clarify whether such underlying assets would also be taxed at 30% or not.

Many times moneys are routed through the exchanges and sometimes it's not apparent who's responsible for deducting TDS on exchange transactions when the buyer and seller can't be identified, if that happens, would the taxpayer be required to figure out who's selling on the other side or buying on this side and comply? This is a real problem that has to be addressed by the government.

Another intriguing aspect is that the new provision states that taxpayers must withhold 1% of the tax on the exchange of virtual digital currency, whether it is entirely on exchange or barter, or partly in cash and partly in exchange. When the cash component is insufficient to cover the 1% TDS, the person in charge of paying must ensure that the recipient, i.e. the seller, has paid the tax. It is unclear how this will be accomplished, whether taxpayers will be required to rely on the CA certificate, the advance tax challan, or some other method. Clarity is required in this regard in order to avoid future contractual and legal litigation.

There has been no clarification provided in the laws regarding the impact of TDS/TCS on global cryptocurrency exchanges. Though it is anticipated that overseas crypto exchanges will not deduct TDS, taxpayers will still be required to pay tax on their crypto gains. If this is not the case, the individual may be prosecuted with tax evasion, which will result in heavy penalties when detected.

In India, more than 100 million people are involved in cryptocurrency exchanges, whereas just 60 million people file their annual income tax forms, according to the government. Now that the finance minister has recognised cryptocurrency exchanges as virtual digital assets and has levied a 30 percent tax on income derived from them, the number of annual returns submitted in India may shoot up very soon.

According to Finance Ministry officials, government will levy goods and services tax (GST) on cryptocurrency transaction fees rather than the digital asset's gross value. The definition of virtual assets in the budget would classify cryptocurrencies or non-fungible tokens as 'intangible goods,' subjecting them to GST.

It is still unclear whether GST will be levied on the margin or the gross value of the virtual asset. As a result, in order to address such anomalies, the government must provide clarification.

Conclusion

Indian government is beginning to recognize crypto as an emerging asset class, and thereby introduction of Crypto tax was a milestone in Indian income tax laws. 30% taxation will have a negligible impact on trifling crypto investors as tax brackets are already similar to regular taxes on short-term securities holdings.

Next issue on the block would be to untangle the GST levy on the crypto transactions. Several state tax officers are definitely working on this thread to identify the areas for which taxation needs to be clarified. We hope with clarification from government on GST by Budget 2023 would add stability to the overall taxation of crypto in India.

Taxation of Virtual Digital Assets – The Finer Aspects

Background

The Reserve Bank of India had reportedly been pushing for a complete ban on all cryptocurrency transactions. In spite of these concerns, investments in digital assets have been rising across the country. Due to the increase in the frequency and volume of transactions of Virtual Digital Assets, for the first time, the provision for the taxation of virtual digital assets is introduced in Budget 2022, bringing Cryptocurrencies & Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) under the tax net.

Basic scheme of taxation under the Act

The Finance Bill, 2022 proposes to tax income from the transfer of Virtual Digital Assets (VDA or VDAs) under section 115BBH. Before any income can be taxed under the Income tax Act, 1961, one has to find out:

- Whether the assessee is an Indian resident or not?

- Whether the situs of the VDA is in India or outside?

- How to determine the situs of the VDA - depending on the residential status or citizenship of the assessee transferring the VDA or that of its miner / creator or based on the place where the exchange is registered or any other factor?

In the absence of guidance on these key aspects, the general provisions of the Act would continue to apply. This means that in the case of determining the taxability of a non-resident in India, one has to take recourse to the general provisions under sections 4 and 5 of the Act. Thus, if the situs of the VDA is not located in India, its income may not be taxable in India.

Having said that, we now proceed to analyse the definition of VDA as proposed by the Finance Bill, 2022. The scope of this article is restricted to the analysis of the definition of VDA under the proposed section 2(47A) and the plausible implications.

Definition of VDA

The proposed section reads as:

‘(47A) “virtual digital asset” means––

(a) any information or code or number or token (not being Indian currency or foreign currency), generated through cryptographic means or otherwise, by whatever name called, providing a digital representation of value exchanged with or without consideration, with the promise or representation of having inherent value, or functions as a store of value or a unit of account including its use in any financial transaction or investment, but not limited to investment scheme; and can be transferred, stored or traded electronically;

(b) a non-fungible token or any other token of similar nature, by whatever name called;

(c) any other digital asset, as the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette specify:

Provided that the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, exclude any digital asset from the definition of virtual digital asset subject to such conditions as may be specified therein.

Explanation.––For the purposes of this clause,––

(a) “non-fungible token” means such digital asset as the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, specify;

(b) the expressions “currency”, “foreign currency” and “Indian currency” shall have the same meanings as respectively assigned to them in clauses (h), (m) and (q) of section 2 of the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999.’.

As one would observe, the definition of VDA is very widely worded. This implies that the Revenue desires to bring to tax digital assets in any form. For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume that we are analyzing whether ‘Gothic’ is a VDA or not.

Coverage

As per the definition, Gothic would be considered as a VDA if it is covered under any of the clauses (a), (b) or (c) above. This means that it may be either:

a. An information or code or number or token meeting the other conditions; or

b. A non-fungible token (NFT) or any other token which is similar to NFT – Explanation to section 2(47A) provides that NFT is a digital asset which is notified by the Central Government; or

c. Any other digital asset as notified by the Central Government.

It implies that if Gothic is not notified under clauses (b) and (c), it may still be covered under clause (a).

Characteristics of VDA for the purpose of clause (a) of section 2(47A)

If Gothic is not a VDA under clauses (b) or (c) of section 2(47A), it may still be considered as a VDA under clause (a). For this purpose, Gothic must be considered as any information or code or number or token which cumulatively satisfies the following conditions:

|

Cumulative conditions |

Points to ponder |

|

It is not an Indian or foreign currency. |

· This implies that India’s own digital currency, as and when recognized, will not be considered as VDA. · Similarly, if any foreign country recognizes Gothic as a currency, it will not be considered as VDA. Currently, El Salvador[1] seems to be the only country which considers cryptocurrency as a legal tender. There is international pressure[2] on the country to withdraw its position. However, until withdrawn, it would be considered as a foreign currency and consequently, not a VDA as per the proposed definition. |

|

It is generated through cryptographic means or otherwise. |

· The term ‘cryptographic means’ is not defined under the Act. In the absence of a clear definition, the matter is prone to tremendous litigation. · The term ‘otherwise’ leads to an interpretation that Gothic may be generated by any means – cryptographic or any other means. This renders the entire limb of the definition meaningless. It would have been appropriate if it was drafted as “generated through cryptographic means or by similar means.” |

|

It can be transferred, stored or traded electronically |

· The words transferred, stored, traded are separated by ‘OR’. · If OR is interpreted as disjunctive in this limb of the definition, there could be some absurd consequences. Eg. - For instance, the points collected in your e-wallet or credit cards are capable of being stored electronically but they cannot be transferred or traded. Will they be covered under the definition of VDA? - Similarly, e-commerce websites like Amazon, OLX help in transferring or trading in goods electronically. But the goods cannot be stored electronically. They have to physically stored. · This implies that the word ‘OR’ appearing in the definition of VDA should be read as ‘AND’[3]. In other words, Gothic can be termed as a VDA if it is capable of being transferred, traded and stored electronically. · Shares and securities are capable of being transferred, traded and stored electronically. A question arises whether they would be considered as VDA based on the proposed definition. This, certainly, does not seem to be the intention of the Revenue – to disrupt the existing scheme of taxation of shares and securities. |

|

It has the following qualities · It should provide a digital representation of value exchanged; or · It should provide a promise or representation of having inherent value; or · It should function as a store of value or a unit of account. |

The points collected in your wallet, credit cards etc. or shares and securities represent a certain value. Unintentionally, they would be covered under this limb of the definition too. |

|

It is used in any financial transaction or investment, but not limited to investment scheme. |

· The term “financial transaction” is not defined in the Act. · A reference may be made to section 285BA(3)[4] of the Act defines which “specified financial transaction” for the purpose of reporting. · Any other transaction which may not be covered in this definition may be covered under the term “financial transaction” as used in general parlance (eg. donations). |

Cryptocurrencies

The proposed amendments do not mention or define the word ‘cryptocurrencies.’ As per the Merriam-Webster’s dictionary:

“Cryptocurrency means: any form of currency that only exists digitally, that usually has no central issuing or regulating authority but instead uses a decentralized system to record transactions and manage the issuance of new units, and that relies on cryptography to prevent counterfeiting and fraudulent transactions”

In real life, cryptocurrencies may be simply used as an investment asset. They are also being accepted as a valid currency in the virtual world. They are being used to:

- Make low-cost and quick money transfers across the globe;

- Make private investments in companies;

- Buy and sell goods or services;

- Play online games or buy new features of the games; or

- Travel worldwide (being considered as a universal currency) etc.

This means that cryptocurrencies can be used as a medium of exchange apart from being considered as an investment or a speculative asset. Thus, not every transaction in cryptocurrencies may be a taxable transaction (eg. NRIs using cryptocurrencies to remit money to Indian relatives). Yet, it may be taxable considering the current drafting of the proposed provisions. It is pertinent to note that the Revenue cannot subject to tax the transactions which are not otherwise taxable under the guise of the VDA regime. Hence, the provisions should be amended to tax the transactions which are in the nature of investment / speculative transactions; the transactions where cryptocurrencies are being used as a medium of exchange should be specifically excluded from the purview.

NFT vs Cryptocurrencies

It may be worthwhile to note that non-fungible token (NFT) and cryptocurrencies are two different things. As per the Merriam-Webster’s dictionary:

Non-fungible token means

a: a unique digital identifier that cannot be copied, substituted, or subdivided, that is recorded in a blockchain, and that is used to certify authenticity and ownership (as of a specific digital asset and specific rights relating to it)

b: the asset that is represented by an NFT

A preliminary analysis of the definition indicates that cryptocurrencies and NFTs are two characteristically different things.

NFTs lead to the creation of digital assets like designs, paintings, graphic characters etc. Digital geeks and students have developed innovative digital designs known as NFTs which have a booming market. The creator owns these assets (akin to patents). These NFTs can be sold outright or retained by the owner to earn royalty from allowing others the 'right to use'. The fact that NFTs can be traded or transacted in cryptocurrencies does not mean that NFTs are cryptocurrencies.

Besides, as the definition of NFT stands today u/s 2(47A), an item may be considered NFT only if it is notified by the Central Government. There are millions[5] of NFTs being traded in the virtual world and new NFTs are constantly being invented. It may not be possible for the Government to notify all these NFTs or the new ones being created. This may lead to unintended consequences of tax arbitrage (explained later in this article) amongst NFTs that are notified and those which are not. Rather, the Government may consider adding NFTs like any other tangible physical assets and the tax treatment accorded must be the same as other tangible assets.

Exclusions from VDA

Proviso to the section provides that the Government may also notify certain digital to be specifically excluded from the purview of VDA. Thus, if Gothic is specifically excluded from the definition of VDA, it will not be taxable under the proposed section 115BBH. This does not mean that it is automatically exempt. It simply means that income from Gothic would be taxable under the normal provisions of the Act which provide for:

- Categorization of income as business income, capital gains or income from other sources

- Benefit of deductibility of expenditure incurred on such income

- Benefit of set-off of losses and carry-forward of losses

- Benefit of slab rates of tax

It may be worthwhile to think whether the proposed definition is opening up the possibility of tax arbitrage by determining whether an asset can be taxed as a VDA or under any other provision of the Act which may prove to be more beneficial.

Virtual digital asset vs digital asset

The definition of VDA uses two terms – “virtual digital asset” and “digital asset”. Usage of 2 different terms would leave open a room for future litigation in the matter.

Our suggestions

It is true that the quantum of trading in VDAs has increased exponentially over the years. People have made money from it and the same should be brought to tax. The Revenue has rightly cleared its stance on the taxation of VDAs. However, the Revenue may be advised well to tread step-by-step on this path. For instance, the proposed definition could have been an exhaustive definition taxing a limited number of VDAs which are clearly identified. Once successfully implemented as a pilot project the definition of VDAs may be further expanded.

[1]https://www.wsj.com/articles/bitcoin-comes-to-el-salvador-first-country-to-adopt-crypto-as-national-currency-11631005200

[2]https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america 60135552#

[3] Judicial precedents have allowed the conjunctive use of the word ‘or’ as ‘and’ under certain circulstances.

[4] “(3) For the purposes of sub-section (1), "specified financial transaction" means any—

(a) transaction of purchase, sale or exchange of goods or property or right or interest in a property; or

(b) transaction for rendering any service; or

(c) transaction under a works contract; or

(d) transaction by way of an investment made or an expenditure incurred; or

(e) transaction for taking or accepting any loan or deposit,”

[5] “we analyse data concerning 6.1 million trades of 4.7 million NFTs between June 23, 2017 and April 27, 2021” - https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-00053-8#:~:text=Conclusion,including%20art%2C%20games%20and%20collectibles.

Cryptocurrency- Key GST Questions Post Budget 2022

This article has been co-authored by Onkar Sharma (Principal Associate, Khaitan & Co).

- Background

While the legality of cryptocurrency / assets in India remains under a shadow of doubt, the following developments in the recent past have once again put a spotlight on the Goods and Services Tax (GST) implications vis a vis various transactions in cryptocurrency / assets:

- Proposal in Finance Bill, 2022 to introduce a new scheme of taxation of ‘virtual digital assets’ (VDAs) to levy income tax and mandate tax withholding at source (TDS) on transfer of VDAs: VDAs have been defined in a wide manner to cover all varieties of cryptocurrencies, NFTs, etc.,

- persons making payments to Indian residents towards the transfer of a VDA, to withhold tax at 1 % on such sum.

- Inspections conducted against 5 (five) crypto-exchanges by the Directorate General of GST Intelligence (DGGSTI) in the last few months resulting in recovery of more than INR 80 (eighty) crores of GST in back-taxes. Per the media reports on the said inspections, the key issue seems to have been non-payment of GST on commissions / facilitation fees earned by such exchanges in certain scenarios, viz.,

- commissions for facilitating transactions by foreigners; and

- transactions where commission was earned in native crypto.

Given the proposal to introduce a new scheme of taxation of VDA’s to levy income tax, a question arises as to whether, it is now possible to infer that under the GST regime, cryptocurrencies / NFTs will qualify as ‘intangible goods’ and therefore, will be liable for payment of GST accordingly. The same has been examined below.

- Nature of cryptocurrency from a GST perspective

Unlikely to qualify as ‘Security’: Securities are specifically excluded from the definitions of both ‘goods’ and ‘services’ under the GST regime. Section 2(101) of the Central Goods and Services Tax Act 2017, (CGST Act) read with the explanation to Section 2(h) of the Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act 1956, defines “Securities” as below:

“Securities include-

(i) shares, scrips, stocks, bonds, debentures, debenture stock or other marketable securities of a like nature in or of any incorporated company or other body corporate;

(ia) derivatives;

(ib) units or any other instruments issued by any collective investment scheme to the investors in such schemes;

(ii) government securities;

(iia) such other instruments as may be declared by the Central Government to be securities; and

(iii) rights or interest in securities.”