Integration of Indian economy with global economy

India began to emerge on the global stage in 1991 with various liberalisation measures relating to industrial licencing, quota system, foreign trade and foreign direct investment. This move towards globalisation brought about new requirements relating to taxation and other laws as many multinational corporations began investing in India and local companies started acquiring companies outside India. The Y2K event made India the service hub to the world as very well explained by Thomas Friedman in his book “The World is Flat”.

In light of the sudden increase of globalisation, an amendment in taxation laws for such transactions between multinational enterprises (MNEs), became the need of the hour so that the tax base for India is not eroded.

The Finance Act, 2001 introduced the Transfer Pricing (TP) regime in India after 10 years of liberalisation by substituting existing Section 92 of the Act and introducing new sections 92A to 92F (w.e.f 1 April 2002) .

The Finance Minister’s speech on the rational for introducing TP Regulations

“The presence of multinational enterprises in India and their ability to allocate profits in different jurisdictions by controlling prices in intra-group transactions has made the issue of transfer pricing a matter of serious concern. I had set up an Expert Group in November 1999 to examine the issues relating to transfer pricing. Their report has been received, proposing a detailed structure for transfer pricing legislation. Necessary legislative changes are being made in the Finance Bill based on these recommendations.”

Rules 10A to 10E were subsequently notified on 21 August 2001.

Income arising from international transactions (IT) amongst associated enterprises (AEs) were now required to be computed at arm’s length price. Methodologies were prescribed to determine the arm’s length price.

The Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) brought revamped rules under chapter X of the Income-tax Act, 1961. The new rules were pivoted on arm’s length price determination for related party transactions through the five standard methods prescribed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Since then, TP in India has taken firm root, with full support of tax administration to verify the arm’s length price. While recounting the developments that have taken place since 2001, it is also time to examine whether the TP practice in India has matured in the last 20 years, and of course, the way forward.

Interplay with Other Laws

Principles of TP were also contained in the Companies Act, 1956 (Sec. 297, S. 299 and S.301) and were also embedded in the concept of valuation under Excise Act and Customs Act in India, which laid down specific rules for valuation in case of transactions between related entities.

Conceptually, both the TP regime and the Customs regulations are designed to determine arm’s length price for transactions between related parties. However, the imperatives of the two regimes are different. While TP regime is a Special Anti-Avoidance Measure, the Custom Valuation Rules are designed to promote global trade with minimum barriers. OECD and World Customs Organisation (WCO) periodically hold summits to bring convergence between the two regimes.

Evolution of the Concept

The world has experienced fundamental changes in international business over the past few decades. Flow of goods and services across countries had increased manifold and there has been larger movement of capital and funds from one country to another. Various trade agreements and regulations under the aegis of GATT and WTO had reduced and removed the quantitative restrictions on movement of goods, services and funds across the countries. Entities not restricting their operations to home market, had expanded rapidly, turning into MNEs and transnational enterprises.

With the growth in global trade, the price at which related parties sell their products, offer services, provide funds or conduct research and development – commonly referred to as TP - has become of interest to tax authorities. Dealings between the entities across international borders, led to issues of proper allocation of income, profits and expenses between the respective tax jurisdictions. The tax authorities of various countries provided mechanism by which they can ensure that they received fair share of the tax based on the economic value added by activities carried out in their country or involving use of assets, infrastructure and skill in that country. As 60% of the world trade is by MNEs and 50% of that is within business groups, TP came to occupy the centre stage of international taxation.

US took lead in introducing aggressive TP legislation backed by an efficient administrative machinery. In order to discourage MNEs to show higher profits in US and lower in their jurisdiction, other countries started introducing comprehensive TP legislation, regulations and administrative set-ups. Developing countries also became aware of the loss to their revenue caused by TP legislation. China also introduced a comprehensive TP system. Hence, in order to discourage the erosion of the tax bases by MNEs such legislations were introduced by many countries by 1990.

An overview of the increase in the number of countries with Transfer Pricing Regulations (TPR) by 2003-2004 is attached in Appendix A.

Origin of Transfer Pricing in India

The concept of TP was not new to India. The Indian Income-tax Act, 1922 had conceptual application of TP principles for the determination of income that would be arising from specified transactions.

In case of CIT vs Abdul Aziz Sahib (7 ITR 647 (Mad)), the Madras High Court estimated the income on the basis of average rate of profits made by other manufacturers and also considered the profits made by the taxpayer in earlier years. (Application of present concept of TNMM and Multi-year analysis)

The Supreme Court (SC) in the case of Anglo-French Textile Company Limited vs. CIT (25 ITR 27) held that there should be allocation of the income between various business operations of the taxpayer company, demarcating the income arising in the taxable territories and without taxable territories. The Court also upheld the apportionment of income between manufacturing and selling operations by holding that profits are not wholly made by act of sale and do not accrue, necessarily at the place of sale. (Significance of present concept of Functions Asset & Risk Analysis)

In the case of Mazagaon Dock Ltd v CIT, (34 ITR 368), the SC held that it would be business of the resident which would be chargeable to tax under the section 42(2) of the 1922 Act, and not the business of the non-resident. It was also held that dealings between the parties formed concerted and organized activities of a business character and the fact that the dealings were such as to yield no profit to non-resident companies, was held to be immaterial.

Section 42(2) of the Indian Income-tax Act, 1922 was replicated as Section 92 of the Indian Income-tax Act, 1961. The principle of dealing at arm’s length is laid down at many places in the Indian Income–tax Act, 1961 e.g.

S. 9(1)(i) - ‘Business connection’ in India and determination of income as is reasonably attributable to the operations in India

S. 40A(2)(b) - Dealings between ‘related persons’ and the ‘concept of fair market value’

S. 80 1A, S. 10A/10B - Close connection between two entities and ‘more than ordinary profits’

S. 92 - Close connection between resident and non-resident and transactions between them producing no profits or less than ordinary profits to resident

S. 93 - Avoidance of income tax by transactions resulting in the transfer of income to non-resident

Arm’s Length Principle

The evolution of the concept of TP had led to the development of internationally accepted Arm’s Length Principle (ALP). It covers cases where there have been undercharging in respect of sale of products and services or funds supplied or overcharging for the product or services or funds acquired, regardless of any resulting shortfall in the tax due to deliberate tax avoidance or merely due to adoption of incorrect pricing methods for taxation purposes. In considering the application of such adjustments, terms of relevant Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA) must be looked into. Most such agreements contain their own provisions to deal with profit shifting arrangements in certain circumstances. These provisions similar to arm’s length TP provisions, are based on the same principle.

The ‘ALP’ as stated in Article 9(1) of the OECD model double taxation convention, provides as under:

“When conditions are made or imposed between associated enterprises in their commercial or financial relations which differ from those which would be made between independent enterprises, then any profits which would, but for those conditions, have accrued to one of the enterprises, but, by reason of those conditions have not so accrued may be included in the profits of that enterprise and taxed accordingly.”

The ALP was laid down on the basis of adjusting profits by reference to conditions which would have existed between independent parties under comparable circumstances. Application of the principles requires that the enterprise be treated as operating as a separate and independent entity. In setting the price to be charged, independent entities would have regard to the functions they are to perform, assets and skills to be used and the degree and nature of business and financial risks involved in the process of deriving the income.

Genesis of TP regulations

The Standing Committee in March 1999 observed that provisions of the Act were inadequate to curb TP among MNEs.

An Expert Group was constituted by the CBDT under Mr. Raj Narain, the then CBDT member, with one professional member in addition to other senior Revenue officers. An Expert Group was set up to bring an efficient TP system that should not only primarily protect the India tax base but also provide a reasonable method for allocating revenue to the concerned taxation jurisdictions.

The Expert Group had discussions with various stakeholders including professional associations, chambers of commerce and industry bodies. The Expert Group also made in-depth study of TP laws of various other countries and interacted with senior Revenue officers of other tax jurisdictions. It also deliberated various relevant issues with OECD. Various thought papers were published and knowledge-sharing sessions were held during the year 2000, some of which are referred here in Appendix B.

OECD Model of TP V. Formulary Apportionment V. Brazilian Model

During an interesting interaction with the Expert Group in the year 2000, along with Deloitte TP specialists from Asia Pacific, the aspect of whether India should follow the OECD TP model of or other options was discussed.

India’s major trading partners and foreign direct investors (US, UK, Germany, France, Japan and South Korea) follow ALP as enunciated by OECD. It was, therefore, advised that India should also follow a similar model as those countries, so as to minimise the administrative burden of documenting the transfer prices and make the process of resolving of TP disputes between countries, efficient.

One is aware of the revocation of the tax treaty between Brazil and Germany few years back due to the inconsistency of application of different TP models.

Recommendation of the Expert Group

After examining the existing provisions in Indian law, the Expert Group felt that Section 92 of the Income Tax Act, 1961 was required to be substituted by a more comprehensive legislation. It would require changes in both substantive as well as procedural laws. Arm’s Length Principle was proposed to be the foundation stone for examining the transfer price of international transactions with AEs.

The entire approach in suggesting various changes in laws and procedures was to safeguard the interest of the Revenue and at the same time to provide an efficient and friendly tax regime to foreign investors in India.

India also entered into agreements for DTAA with various countries. These treaties generally included specific Article(s) (generally Article 9) dealing with AEs. While Article 9 had fairly wide magnitude, its applicability in India was debatable because its effect was considerably diluted in terms of the provisions of then Section 92 of the Income Tax Act, 1961. A need was thus felt to incorporate into the Act, a specific chapter on TP. Also, with the increase in anti-dumping measures by various countries, principle of TP was assumed to be of greater importance.

The fact was that the erstwhile provisions of Section 92 was quite vague with terms such as “close connection” not being defined. Furthermore, no detailed methodology was also prescribed to compute what was considered as “ordinary profits”. This lack of overall clarity and fundamental change in international business led to the evolution of the “TP” regime in India.

The Government of India in order to have real time mechanism for testing of the related party transactions created a separate post of Directorate of International Tax to deal with the complex issues of TP. To ensure smooth implementation of TPR, the CBDT was taking assistance from OECD for training of tax officials as a capacity building measure.

Methodologies

The following methods have been prescribed for determination of the arm’s length price:

· Comparable uncontrolled price method;

· Resale price method;

· Cost plus method;

· Profit split method;

· Transactional Net Margin Method;

· Such other methods as may be prescribed (with effect from 1 April 2012).

Documentation

A set of extensive information and documents relating to IT undertaken is required to be maintained, on an annual basis.

It was also mandatory for all taxpayers, to obtain an independent accountant’s report in respect of all IT.

Penalty

Penalty provisions were introduced for failure to maintain the prescribed documentation or failure to furnish the prescribed report from an accountant as also for TP adjustments.

Though the penalties prescribed are substantially higher than other countries, in practice the provisions are more as deterrents rather than actual levies.

Assessment

A separate cell consisting of TP Officers (TPOs) was set up under the Director of Transfer Pricing for the purpose of determining the arm’s length price for taxpayers. The Assessing Officer was empowered to refer the determination of the arm’s length price for IT, to the TPO.

TP adjustment for any resulting shortfall in tax can be due to tax avoidance or merely due to adoption of an incorrect pricing method for taxation purposes. As experienced in other countries, the India TP regime has been maturing with learnings from various assessments leading to various alternative dispute resolution mechanisms and adoption of international best practices.

Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

In addition to the normal appeal process of CIT(A), considering the significant TP disputes, the Dispute Resolution Panel (DRP) was set up as an alternate dispute resolution mechanism.

Other Alternative Dispute Resolution was introduced in 2012 by way of the Advance Pricing Agreements scheme. TP disputes are also resolved under the Mutual Agreement Procedure, under the relevant article of the tax treaty between the two countries.

Safe Harbour regulations were also introduced in 2009 to reduce litigation and provide certainty to taxpayers while reducing the administrative burden.

The tax authorities are adopting enhanced approaches such as adoption of practices suggested under BEPS Action Plans, following a risk-based tax audit approach or a faceless assessment or appeal; these have further strengthened the TP mechanism. During the past few audit periods and outcomes from appeals before appellate forums, the Revenue has been adopting innovative ways to view a particular transaction and experiences from APA as well as CbCR have also boosted the tax policy framework. Tax authorities are also looking at capacity building by the use of technology, artificial intelligence and data analytics.

There have been a number of judicial opinions wherein TP disputes have been examined and crucial legal principles have evolved over these two decades.

What’s lies ahead?

The regulations on TP were clearly inevitable. While there can be no denial of the necessity of setting a framework for TP, it was always expected that TP in future would carry more tax exposure due to aggressive and sometimes conflicting positions of tax authorities of various countries. The documentation approach was also expected to produce reasonable results with minimal tax exposure, while dealing with TP assessments. TP was also expected to help in the proper evaluation of the performance of economic activities carried out by various affiliates and assist in managerial decision making.

Two decades since its introduction in India, the TP regime has evolved and matured significantly. India is also a very active member of G20 initiative under aegis of OECD on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). India has also introduced the three-tiered TP documentation approach as per BEPS Action Plan 13, and has also brought in other approaches from BEPS Action Plan, e.g., exchange of CbCR, concept on Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection and Exploitation, Thin Capitalisation rules etc.

With BEPS-related regulations being implemented in India and worldwide, and with more information at the disposal of the tax authorities, tax authorities are expected to be extensively scrutinising MNE businesses. Taxpayers will likely need to have robust underlying documentation and ensure that their global TP policies are aligned to local TP policies in various jurisdictions.

The TP regime has evolved via a consultative manner right from its inception of the Expert Group in November 1999. In fact this led to a consultative approach amongst various stakeholders in other Direct Tax and Indirect Tax areas. Adherence to TP regime in India by all stakeholders – taxpayers, professionals and tax administrators in a collaborative manner will be helpful as India makes it contribution in the forthcoming decade, widely believed to favour Asia and to achieve its potential of becoming a US$ 5 trillion economy in the near future.

To summarise, while we have traversed 20 years of TP, it is time to think on how to improve its working and provide a basis that leads to its maturity. The inward FDI into India has increased from US $75 million in 1991 to US $42,285.68 million in 2018, registering an annual average growth rate of about 38%. With the government pushing the envelope further, we would soon see larger MNEs’ participation in India, which would certainly call for a modern transfer pricing regime, with global standards not only in law but also in practice.

Appendix A

Navigating MAP Procedure

ALP in Cyberspace - Appendix B

Reconciling Treaty with Domestic Law - Appendix B

Stress on TP Documentation - Appendix B

Transfer Pricing Rules - Appendix B

Introduction

Financial Year 2020-21 culminates two decades of Transfer Pricing regulations (“TP regulations”) in India. The detailed TP regulations were introduced in India vide Finance Act, 2001, by insertion of sections 92A to 92F in the Income Tax Act, 1961 (“the Act”) and since then, there has been constant evolution not only in the legislation but also in its practical application by key stakeholders such as appellate authorities, tax authorities, taxpayers and tax practitioners.

With maturity of legislation and application by stakeholders, functional analysis i.e. an analysis of functions performed, assets employed and risks assumed (FAR) analysis of related party transactions has emerged as the cornerstone for determination of arm’s length margin/ price.

Genesis and Concept of FAR Analysis

The concept of arm’s length principle in itself is not new and its origins can be found in the contract law which propounded for an equitable agreement that will stand up to legal scrutiny, even though the parties involved may have shared interests.[1] Over the years, arm’s length principle gained recognition in international taxation and was adopted by OECD and the UN model tax conventions as the basis for bilateral tax treaties. Article 9(1), while seeking to adjust profits between related parties in reference to the conditions between independent enterprises in comparable transactions and circumstances, established the concept of comparability analysis as the heart of the arm’s length principle.[2] In order to compare the conditions made or imposed between related parties with independent enterprises, accurate delineation of the transaction and for ascertaining the functions undertaken, assets utilised and the risks assumed by the transacting parties, a FAR analysis is required to be undertaken. The detailed TP guidance issued by OECD and UN also discussed several aspects with regard to the importance and applicability of FAR while undertaking comparability analysis.

With the advent of concept of arm’s length and comparability analysis in the international forum, the principle was also adopted by several countries as part of their domestic tax regulations. In the Indian context, prior to introduction of detailed TP regulations in 2001, the lone Section 92 of the Act, while proposed an arm’s length principle, but did not provide any detailed guidance with regard to undertaking a Transfer Pricing (TP) analysis. The Government of India, vide Finance Act, 2001 introduced detailed TP regulations, as enshrined under Section 92A to 92F (read with relevant rules).

In these detailed TP regulations as well, the importance of FAR analysis is deeply engraved as it forms the basis for the following key aspects of an arm’s length analysis:

· Selection of the most appropriate method- Each of the TP methods prescribed[3] have certain attributes associated with them which make them more suited for a particular fact pattern. FAR analysis helps in identifying such attributes which are then used for selecting the most appropriate method.

· Selection of the tested party – For application of any one-sided TP methods (i.e. Cost Plus Method, Resale Price Method or Transactional Net Margin Method) one of the transacting party is selected as the tested party. Generally, such tested party is the least complex entity in relation to the transaction, which undertakes simple operations, does not own unique intangibles and its financial data is easily available for undertaking an accurate arm’s length analysis.[4]

· Selection of independent comparable companies/ transactions – A detailed FAR analysis of an accurately delineated transaction also helps in identifying key comparability factors that need to be evaluated while selecting independent comparable companies/ transactions.[5]

· Ascertaining if any economic adjustment is required to be undertaken– While FAR analysis forms the basis of evaluating the appropriateness of selecting independent comparables/ transactions, it also becomes relevant for identifying the need for undertaking any economic adjustments (such as working capital, risk, capacity adjustments, etc.). Such adjustments are required to be undertaken to eliminate the impact of any differences between the tested party and the comparable companies/ transactions and thus helps in improving comparability.[6]

A detailed FAR analysis is also required to be documented by all taxpayers as part of annual compliance documentation (“TP Documentation”) along with comparability analysis undertaken to demonstrate the arm’s length nature of related party transactions.[7] Considering the above, it can be seen that FAR analysis forms the basis of several important aspects of an arm’s length analysis.

Having discussed FAR as a concept and its relevance, let us now look at application of FAR during TP audits.

FAR and TP audits

TP documentation maintained by taxpayers, capturing the FAR and arm’s length analysis, is one of the key documents requested by Transfer Pricing Officers (“TPOs”) during TP audits. It provides the contemporaneous analysis undertaken by the taxpayer for establishing the arm’s length nature of related party transactions.

The approach of TPOs, while evaluating the said TP documentation, has also evolved over the years. During the initial cycles of TP audits, due to lack of sufficient resources (in terms of technical knowledge, experience, tools, manpower, etc.) with the TPOs, the primary focus was on superficial/ quantitative issues of comparability and arm’s length analysis. Such issues included:

· Use of single versus multiple year data – As a thumb rule, the use of multiple year data by taxpayers was rejected by TPOs, without appreciating whether business cycles actually have an impact on the functional profile, business activities and the results earned by the comparable companies.

· Selection of TP method – In several cases, for instance, involving distributors, the gross level analysis undertaken by taxpayers (under Resale Price Method/ Cost Plus Methods) was rejected by the TPOs in favor of net level testing, while ignoring that specific attributes of the taxpayers’ operations warranted a gross level testing.

· Classification of income/ expenses as operating or non-operating, etc. – Often TPOs arbitrarily treated certain items of income/ expenses as operating/ non-operating (for example foreign exchange gain/ loss) without appreciating the functions undertaken and risks assumed by the taxpayer and the understanding between the parties as borne out by their conduct with regard to such expenses / income.

· Arbitrary classification of taxpayers’ operations as high-level/ complex – In certain cases, routine operations of taxpayers were arbitrarily classified as high-level/ complex functions, without appreciating the level of contribution made by the taxpayer in the overall value chain of the group.

While the TPOs focused on quantitative aspects, there was less focus on functional attributes of the taxpayers and corresponding issues emanating from them. This led to a large number of TP adjustments being proposed, without taking into cognizance the specific facts and circumstances of the taxpayers. More often than not, these specific facts and circumstances, which had been documented by taxpayers as part of their FAR analysis, were appreciated by higher appellate authorities, thereby resulting in deletion of adjustments proposed.

Despite the quantitative approach adopted by on-ground officers, the higher appellate authorities appreciated the importance of a FAR analysis early on in the journey of TP regulations in India. The importance of a robust FAR analysis was established in the landmark case of Mentor Graphics[8] wherein it was held that selection of comparables is to be made considering the specific characteristics of the controlled transaction, functions performed and assets deployed (including intangibles) rather than just a broad comparison of category of activity undertaken.

With time, as more guidance[9] and technical tools were available to the TPOs, a shift was seen towards a more qualitative approach. As part of such approach, the TPOs also started appreciating the importance of aligning any TP adjustment to the case specific facts and FAR profile of the taxpayer. In fact, in several cases it was seen that TPOs also supplemented the FAR analysis undertaken by the taxpayers further, with additional information that is available in the public domain, as follows:

· Evaluating functions performed by key personnel of the taxpayers – Rather than placing reliance only on the documented FAR analysis, the TPOs in certain cases interviewed key personnel of the taxpayer to understand their roles and responsibilities and to understand the contribution of the taxpayer in the overall value chain. They also conducted internet searches on public platforms such as LinkedIn to gather details of such personnel regarding educational qualifications, experience, job profiles, etc. This was observed in the case of GE Energy,[10] wherein despite taxpayer’s documented submission that their the liaison office in India was only engaged in communication channel activities, the tax authorities summoned several key personnel of the taxpayer and perused their LinkedIn profiles to evaluate their roles and responsibilities and ascertain their contribution in the overall value chain. Based on the statements of employees and analysis of documents, the tax authorities alleged that the liaison office constituted a Permanent Establishment in India as it was engaged in rendering services to overseas group entities and thus, the income attributable to such Permanent Establishment was taxable in India. These LinkedIn Profiles were subsequently admitted and accepted by the higher authorities as additional evidence.

· Evaluating contribution by taxpayer in overall value chain – In a few cases, the TPOs evaluated the contribution made by the taxpayer to patents / technology/ IP developed and registered in the name of overseas related parties by analysing patent filings and other regulatory documents available in the public domain. Such an approach is also evident from certain Tribunal[11] rulings, wherein based on patent filings with the name of Indian employees available in the public domain, the tax authorities re-characterised routine software development functions performed by the taxpayer as high-end contract research and development services. This was in complete contradiction to the FAR profile documented by the taxpayer, which involved rendering of routine software development services in the nature of testing and coding services.

It can be seen that with the evolving TP landscape, an approach which considers both quantitative and qualitative aspects of the taxpayer is being adopted by the tax authorities. The tax authorities are also learning from detailed FAR analysis, experiences gained under the Advanced Pricing Agreement (APA) programme. With such an approach, complex issues are being identified and litigated upon, these include marketing intangibles, location saving, applicability of complex methods such as profit split method, etc. The genesis of such issues is linked to the functions performed and the contribution made by the taxpayer to the overall value chain of an MNE group. In cases where the taxpayer had undertaken a detailed FAR, backed up by contemporaneous documentary evidences, and an appropriate arm’s length analysis based on such FAR, the appellate authorities are more inclined to accept the same. However, in cases where a detailed FAR was not provided or the FAR did not seem to correspond to the actual conduct, the appellate authorities either reject the taxpayer’s contentions or remand the matter back to the lower authorities for accurate determination of FAR.

With the enhanced skillset and experience, Indian tax authorities are catching up to the global standards of TP. However, there still seems to be a long road ahead with the global landscape evolving regularly. In this regard, key global developments on account of FAR analysis which would have an impact on how the same is viewed by tax authorities, are discussed below:

Global developments

Aligning Returns to Value Creation

The OECD under Actions 8-10, of G-20 BEPS[12] initiative, proposed valuable guidance to ensure that allocation of profits is aligned to value creation by the respective transacting parties. The above guidance placed greater emphasis on actual conduct of the parties instead of merely relying on the contractual terms agreed between them. This approach provided for a more granular FAR analysis, based on actual conduct, decision making and capacity to control and bear risks by the transacting parties instead of placing reliance on inter-company agreements.

Three Tiered Documentation - Enhanced Focus on Transparency

The OECD under the BEPS initiative also identified transparency of information as one of the key measures to tackle BEPS. Accordingly, under Action 13, of G-20 BEPS initiative, the OECD proposed a three-tiered documentation structure consisting of Local File, Master File and a Country-by-Country report.

Given that the three-tiered documentation structure requires taxpayers to provide information regarding global supply chain, key value drivers of the business, intangibles and R&D related contributions, etc., it is no longer sufficient to undertake an isolated FAR analysis for a transaction. Instead, it is important to undertake a detailed Value Chain Analysis of the entire group to understand how value is created by the MNE and to analyse if allocation of profits is in line with the contribution made by the taxpayer towards such value creation.

Digital Economy- From FAR to FARM

One of the key thrusts of OECD under the BEPS initiative was to identify and evaluate cases of digitally enabled MNEs which may have a significant market presence in a particular jurisdiction and may engage with the user base without even having a legal/ physical presence in that jurisdiction. In this regard, the OECD identified that apart from a FAR analysis, relevant importance is also required to be given to contribution made by the underlying market (M). This led to a further evolved variant of the FAR analysis into a FAR(M) analysis, which not only required a detailed FAR analysis but also an in-depth analysis of the MNE group’s engagement with the market and the contribution made by users of such market towards value creation. The recently released Pillar One blueprint by OECD also acknowledges the importance of both FAR to ascertain “material and sustained contributions” by entities to group’s residual profits and of a market linked analysis, while allocating tax liability to entities having “market connection” to eliminate double taxation.

Conclusion

The journey of TP regulations in India has been of evolution. While the Indian TP landscape has evolved and certainly matured, it is still catching up to the fast evolving global landscape. It would be interesting to see how the next decade turns out for TP, especially considering the recently introduced provisions for risk-based and faceless assessment. It is expected that the relative importance of a well-documented FAR analysis would grow manifold with a central team being constituted for selection and evaluation of complex cases for scrutiny and with limited face-to-face interaction with TPOs.

[1] United Nations Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing (2017) Para B.1.4.3

[2] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development TP Guidelines (2017) Para 1.6

[3] Rule 10C(2) of Income Tax Rules 1962 (“the Rules”)

[4] Rule 10C(2)

[5] Rule 10B(2)

[6] Rule 10B(2) r.w. Rule 10B(3)

[7] Rule 10D(1)(e)

[8] Mentor Graphics (Noida) Private Limited v. DCIT in (2007) 109 ITD 101

[9] Such as CBDT circular no. 03/2013 “Conditions Relevant to Identify Development Centers Engaged in Contract R&D services with Insignificant Risks”, amended vide circular no. 06/2013

[10] GE Energy Parts Inc. v. ADIT (ITA No. 671/DEL/2011)

[11] Income Tax Appellate Tribunal

[12] Base Erosion and Profit Shifting

Almost two decades after the introduction of transfer pricing (TP) regulations in 2001, the Indian TP space has evolved immensely. Working capital adjustment, although a mature concept now, has passed under the lenses of all stakeholders in TP and has developed over the years in India. While working capital adjustment to an arm’s length price has always remained important, its significance and impact in TP has been acknowledged gradually over the years.

Background

The cornerstone of transfer pricing provisions is to determine/ arrive at appropriate arm’s length price/ margin (“ALP”) for intra-group transactions.

Indian regulations specify six methods that can be applied to determine the ALP. All of these methods, except for the CUP (comparable uncontrolled price) and other method, involve comparison with comparable uncontrolled companies (herein referred as ‘comparables’), wherein the profit margins of these companies determine the applicable arm’s length margin range (normally referred to as transaction profit methods).

The ALP determination, based on comparability methods, often requires economic adjustments to consider business realities of comparable companies, as the selected comparables may belong to varied economic conditions and there may be different set of economic arrangements and policies vis-à-vis the tested party (typically the taxpayer).

Therefore, with an intention to enhance the comparability analysis, rule 10B(3) of the Indian Income Tax (I-T) Rules, 1962, in line with international practices, allows for economic adjustments / comparability adjustments to adjust for the differences (if any) between the tested party vis-à-vis the comparables. Further, Chapter III of the revised transfer pricing guidelines issued by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2017 and United Nations Practice Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing countries, 2017 (UN Manual) also recommends comparability adjustments, if (and only if) they are expected to increase the reliability of the results.

One of the most carried out comparability adjustment in transfer pricing is working capital adjustment.

What is working capital adjustment and why is it important in TP?

Working capital adjustment is an adjustment for the opportunity cost of capital for investments made in working capital (i.e. inventories, accounts receivable/debtors and accounts payable/creditors) of a taxpayer. It is undertaken when a taxpayer or the tested party exhibits different working capital intensities relative to a set of comparable companies.

Working capital adjustments seek to adjust for differences in time value of money between tested parties and potential comparables as the difference should be reflected in profits because high levels of working capital create costs either in the form of incurred interest or through opportunity costs.

Practical example

I Co Private Limited (ICo) is a wholly owned subsidiary of a Multi-National Enterprise (MNE) which is headquartered in UK. ICo primarily functions as a captive unit in India and is engaged in rendering routine software development services only to its parent entity (and no other entity) and operates on a remuneration model of total cost (direct plus indirect cost) plus a mark-up of 17%.

The ICo receives its remuneration from its parent company, on an average, in 60 days. ICo takes on an average, 120 days to pay its creditors. Thus, it can be seen that the average payment period of ICo is greater than its average debtors’ collection period, thereby giving it a negative working capital requirement position.

On the other hand, the average receivable period of uncontrolled comparables which are engaged in rendering similar software development services, has been found to be 90 days whereas their average creditors payment period is 60 days.

Thus, it can be seen that the comparables are carrying a relatively high working capital position as compared to ICo as the said comparables are allowing their customers a relatively longer period to pay their accounts while they are paying their creditors in a relatively lesser time frame.

Therefore, it can be deciphered that the working capital cycle of ICo is less aggressive and shorter vis-à-vis comparables and as a result, the comparables would be making higher sales revenue to account for the cost of borrowed capital. As a result, the comparables would be earning high operating profit margins compared to ICo.

Taxpayers, such as captive service providers or contract manufacturers, who principally operate on a cost plus mark-up remuneration based model, or a limited risk distributor who principally earns an assured return on sales, are typically in a position to receive advances for services to be provided in future, thereby having lower working capital position vis-à-vis comparables. On the other hand, comparable companies are typically unlikely to receive such advances and hence in such cases they tend to account for it in the form of higher sales price which eventually leads to higher operating profit results of comparables, when the comparison is drawn. Therefore, adjustments have to be made to make the transactions comparable.

In other words, no profit maximising/entrepreneurial company would hold working capital without an additional return as working capital yields a return resulting from a) higher sales price or b) lower cost of goods sold which would have a positive impact on the operating profit margin.

Thus, the principal objective of working capital adjustment is to eliminate interest element embedded in sales and cost of goods sold.

In practice, the working capital adjustment is usually done when applying a transactional net margin method (“TNMM”), although it could also be applicable in cost plus or resale price methods.

Global acceptability

Chapters I and III of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for MNEs and Tax Administrations 2017 (herein referred as ‘OECD TP guidelines’) contain extensive guidance on comparability analyses for transfer pricing purposes. The annexure to Chapter III of the OECD TP guidelines discusses the need and process of performing working capital adjustment.

According to the United Nations Transfer Pricing (UNTP) Manual, comparability adjustments can be divided into the following three broad categories:

- Accounting adjustments

- Balance sheet/working capital adjustments

- Other adjustments

The most important amongst them is balance sheet /Working Capital Adjustments. Balance sheet adjustments are intended to account for different levels of inventories, receivables, payables, interest rates etc. The most common balance sheet adjustments made to reflect different levels of accounts receivable, account payable and inventory are known as working capital adjustments.

Working capital adjustment in India – journey so far

In many cases, Transfer Pricing officers did not accept the rationale for applying working capital adjustment. The different arguments provided by TPOs can be summarised into the following buckets:

· The analysis provided by the taxpayer did not demonstrate that an adjustment for working capital differences has improved comparability in the said case;

· TNMM method allows broad flexibility tolerance in the selection of comparables and hence no further adjustment is required;

· The adjustment does not significantly impact the average margins being earned by the comparable companies

Additionally, for service providers, tax authorities were of the view that the issue of difference in working capital was more pertinent for manufacturers or distributors where inventories are tied up, unlike in case of service providers who start working on projects only after a contract is awarded.

All these observations led to a more detailed and nuanced analysis, wherein the need and benefits arising from the economic adjustments from working capital adjustment were explained and discussed. The litigation around such adjustment was also the result of other factors such as:

· Absence of specific provision allowing working capital adjustment: Rule 10B of Income Tax Rules, 1962, which deals with determination of arm’s length price under section 92C, permits comparability adjustments. However unlike OECD, there has been no specific provision or rule under Indian Income Tax Act or Rules discussing or describing working capital adjustments and how to perform them.

· No common formula suggested under law: There was no guidance in law on the appropriate formula to be adopted

Some factual and methodology related aspects on this topic started getting settled through decisions by Hon’ble ITAT in several cases.

In these rulings, the ITAT held that an adjustment needs to be made to the margins of comparable companies to eliminate differences on account of different functions, assets and risks. More specifically, the adjustment needs to be made for (a) differences in risk profiles, (b) differences in working capital position and (c) differences in accounting policies. Thus, conducting a working capital adjustment in a competitive environment is important and relevant to improve comparability. As on date, there are numerous decisions of Tribunal allowing working capital adjustment. However, in some rulings, working capital adjustment has also been denied stating that the onus of proof is on taxpayer to demonstrate the such adjustment is necessary and improves comparability.

It is also settled by numerous decisions that working capital adjustment are also to be provided for service industry.

There have been instances, when in case of captive service providers, the department has made negative working capital adjustment to the detriment of the taxpayer. There is plethora of judgements which hold that negative working capital adjustments are not warranted in case of captive service providers with no working capital risk.

Following this evolution through domestic jurisprudence, in the current environment, Indian taxpayers as well as tax authorities follow the formula prescribed by OECD guidelines for carrying out working capital adjustments.

A snapshot of the process of computing working capital adjustment as per OECD is given below:

|

Working capital adjustment |

Reference |

Financial Year 1 |

|

Tested party’s (R+I-P)/Sales |

[A] |

26% |

|

Comparables’ (R+I-P)/Sales |

[B] |

30% |

|

Difference |

[C=A-B] |

4% |

|

Interest rate |

[E] |

10% |

|

Adjustment |

[F=C*E] |

0.40% |

|

Comparables’ OP/Sales (%) |

[G] |

1.32% |

|

Working capital adjusted OP/Sales for comparables |

[H=G+F] |

0.92% |

R = Receivables; I = Inventory; P = Payables; OP = Operating Profit

Working capital adjustment and the TP litigation on inter-company receivables

Over the last few years, tax authorities have been consistently taking the stand that an overdue balance receivable by an Indian enterprise from its overseas AE is akin to interest free loan advanced by the Indian entity to its overseas AE.

After being litigated for several years, the question whether inter-company receivables is to be treated as a separate international transaction or not, was addressed by way of a retrospective amendment (w.e.f. April 2002) by the Ministry of Finance vide the Finance Act 2012, wherein the amendment was made to the definition of ‘international transaction’, to include “capital financing, including any type of long-term or short-term borrowing, lending or guarantee, purchase or sale of marketable securities or any type of advance, payments or deferred payment or receivable or any other debt arising during the course of business”.

Tax authorities claim that by carrying high accounts receivable, a company is allowing its AEs a relatively longer period to settle their accounts. It would need to borrow money to fund the credit terms and/or suffer a reduction in the amount of cash surplus which would have been otherwise available for investment. In this case, tax authorities consider any amount outstanding for more than a normative period, generally 30 days, as being in the nature of a loan arrangement and impute a notional interest on such outstanding amounts.

However, most taxpayers have claimed that outstanding debtor balances are not a separate transaction and arise out of primary transaction of sales and/ or service income. Taxpayers have also considered that even if the debtors are considered as separate transaction, the benchmarking should be an integrated analysis as the transactions are interrelated. Therefore, under a TNMM (or RPM or CPM) analysis, the working capital adjustment addresses the concern of benchmarking inter-company receivables. The taxpayers claim that if after performing working capital adjustment, the margin of tested party is more than the adjusted margin of comparable companies, it can be concluded that the prices charged by the taxpayer includes an embedded interest element to reflect the extended credit terms.

In various rulings, this approach of working capital adjustment has been accepted as a reliable measure to substantiate the arm’s length nature of inter-company receivables. The Delhi Tribunal[1] held that the impact of delayed receivables from AEs are subsumed in working capital adjustments made by the taxpayer. This decision of ITAT was also confirmed by the Delhi High court.[2] It may be noted that the concept of embedded interest element in profits, on account of credit/payment period, has been accepted in APAs also, wherein the agreed arm’s length profit margin may vary, per agreed credit period.

Further in case of a debt-free company, the Delhi Tribunal[3], held that no adjustment can be made in respect of notional interest on outstanding receivable. The above decision has further been affirmed by the Hon’ble Delhi High Court[4].

Important aspects to be kept in mind

Average or year-end balances: A key issue in making working capital adjustments is the time when the receivables, inventory and payables are compared between the tested party and the comparables. Averages might be used if they better reflect the level of working capital over the year. There are judgements which have held that insisting on daily balances of working capital to compute working capital adjustment is not proper as it will be impossible to carry out such exercise and that working capital adjustment has to be based on the opening and closing working capital deployed. Further, with the introduction of concept of weighted average and multiple year analysis in Indian Transfer Pricing Regulations, the weighted average of three years of each item i.e. receivable, inventory and payable may be computed for comparable companies vis-à-vis current year data of tested party, in the similar manner as prescribed for comparison of unadjusted weighted average margins.

Interest rate: Another major issue in making working capital adjustments involves the selection of the appropriate interest rate (or rates) to use. The rate (or rates) should generally be determined by reference to the rate(s) of interest applicable to a commercial enterprise operating in the same market as the tested party. In most cases, a commercial loan rate will be appropriate. In India, in our experience, the tax authorities generally prescribe SBI[5] base rate or prime lending rate or MCLR[6] as on June 30 of the relevant year. It may be noted that while APA[7] authorities do not provide for working capital adjustment. However they generally allow a credit period (period is based on case to case) and thereafter prescribe an interest rate on overdue receivables, which is generally 6 months LIBOR or PLR of the currency in which the billing is done, plus 300 to 400 basis points; the Delhi High Court[8] has upheld the direction given by the ITAT[9] of not using the prime lending rate considering the taxpayer was receiving only in foreign currency.

Other current assets/liabilities: Another question that arises is what to include for the purpose of calculating receivables and payables for working capital. Apart from sundry debtors and sundry creditors, there are other current assets and liabilities items in the balance sheet such as advance from customers, advance to suppliers, etc. which are also considered for calculation of working capital.

Conclusion

Based on the above, it can be said that finding a perfect comparable for benchmarking purposes, i.e. having a FAR profile similar to the taxpayer, is a daunting task as no two independent entities are exactly similar in today’s perfect competition. Hence, working capital adjustment is necessitated for the purposes of improvement of comparability, wherever required. In India, judicial principles have provided clarity on some key aspects on working capital adjustment and this has been helpful in reducing disputes between taxpayers and tax authorities over time.

*****

Background

In today’s ever transforming and competitive world environment, companies have to carve out a niche in the marketplace to remain competitive and stand out as differentiators. The world economy has moved towards globalisation and digitalisation. The key value drivers of a business today include digital assets, brand/trademark, technical knowhow, etc. All these may include, inter alia, what are commonly referred to as “intangible assets”.

Definition of intangibles under Indian TP law

Section 92B (1) of the Indian Income Tax Act 1961 provides the definition of an international transaction as a transaction between two or more associated enterprises (AEs), either or both of whom are non-residents, in the nature of purchase, sale or lease of tangible or intangible property, or provision of services, or lending or borrowing money, or any other transaction having a bearing on the profits, income, losses or assets of such enterprises.

A specific reference to intangible property was provided in this clause to include within the ambit of Indian TP regulations.

The Finance Act 2012, further amended section 92B wherein an explanation was added and specific inclusions to the definition of “international transactions” were provided. In addition to other inclusions it specifically provided that “the purchase, sale, transfer, lease or use of intangible property, including the transfer of ownership or the provision of use of rights regarding land use, copyrights, patents, trademarks, licences, franchises, customer list, marketing channel, brand, commercial secret, know-how, industrial property right, exterior design or practical and new design or any other business or commercial rights of similar nature” would be covered under the scope of an international transaction. Further, it was also categorically provided that the intangible property would include intangibles related to marketing, technology, artistic, data processing, engineering, customer, contract, human capital, location, goodwill, methods, procedures, customers lists, technical data and any other item that derives its value from intellectual content. It is also interesting to note here that these clarifications were brought in as a retrospective amendment.

Transfer Pricing and intangibles

Transfer pricing of intangibles is a vexed issue that has not only perturbed taxpayers but has also caught the attention of tax authorities. Discussions have revolved around what should be the arm’s length remuneration that a legal owner of an intangible be provided; what arm’s length remuneration that other group entities to which functions relating to development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation (DEMPE functions) of intangibles have been outsourced by the legal owner, should be allocated and taxed in the their relevant jurisdictions? Like in other situations, tax authorities are keen to see that transactions related to intangibles are structured between AEs such that they are reflective of an arm’s length scenario as exists between uncontrolled independent enterprises.

What is important here is to accurately delineate the transactions related to intangibles and understand the following aspects prior to undertaking an economic analysis for any transaction pertaining to intangibles:

- Identification of the legal owner of the intangibles

- Identification of the relevant entity/entities of the MNC Group which have contributed to the development of the intangibles,

- Identification of the entity/entities which have exploited those intangibles and to what extent,

- Distinction between legal owner and the economic owner,

- Which entity/ jurisdiction should actually be allocated the profits/ losses arising out of the commercial exploitation of the intangibles?

Definition of intangibles in OECD

In order to address TP issues related to intangibles, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) released Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Action Plan (AP) 8-10 titled “Aligning Transfer pricing outcomes to value creation” in October 2015. The principles suggested in the BEPS AP 8-10 are reflected and were confirmed in the 2017 edition of OECD TP guidelines.

This guidance broadly deals with explanations to ensure that the profits and returns generated by valuable intangibles be allocated to the economic activities that result in value creation.

A broad and clearly delineated definition of intangibles has been adopted in BEPS AP 8-10 and correspondingly in Chapter VI of the OECD 2017 (Para 6.6) and provides that “the word “intangible” is intended to address something which is not a physical asset or a financial asset, which is capable of being owned or controlled for use in commercial activities, and whose use or transfer would be compensated had it occurred in a transaction between independent parties in comparable circumstances.” An illustrative list of intangibles has been provided in para 6.18 to 6.27 which includes patents, know-how and trade secrets, trademark, trade names and brands, rights under contracts and government licenses, licenses and similar limited rights in intangibles, goodwill and ongoing concern value. It has also been provided in para 6.30 and 6.31 that group synergies, market specific characteristics are not considered as intangibles for TP purposes since these are not capable of being owned or controlled but can be value drivers for a business. The guidance suggests that these factors may instead be considered as the basis for making any TP adjustments during a comparability analysis.

For the purpose of TP analysis, the identification of an intangible cannot solely be determined by its characterisation by the taxpayer or for any legal/ accounting purpose but has to satisfy the conditions mentioned in the OECD definition. An item may not be an intangible from tax/ accounting purpose but may be an intangible from a TP perspective and hence may require detailed examination and TP analysis. A common example is where research and development (R&D) expenditure may be expensed in the P/ L account and not capitalised for accounting purposes and hence the intangibles may not be reflected in the accounting books. However, the investment made by a company in R&D may create significant economic value for the group and therefore the contribution of the entity undertaking R&D functions to group profits may need an evaluation from a TP perspective. In other words, from a TP perspective, evaluation would be required whether the entity can be considered to contributing to enhancing the value of intangibles by undertaking DEMPE functions (in as much as it may also have the capacity to make decisions and assume risks arising out of the DEMPE functions). This analysis will then enable evaluation of the appropriate transfer pricing method that should be applied in such transactions e.g. whether Profit Split Method (PSM) needs to be applied or whether a differentiated mark-up on costs of services can be considered.

Circular 6/2013: Precursor to DEMPE

The Central Board of direct taxes (CBDT) in India had issued a circular no. 6 which gave a preview into the concept of DEMPE functions in 2013. This was much before the OECD formally issued its guidance on DEMPE. The said circular classified the R&D centres of the foreign groups in India into three broad categories i.e. entrepreneurs, joint developers and risk insulated contract R&D centres. This was done basis the functions, assets and risks of the centres established in India. The circular, inter alia, laid down certain guidelines for characterising the development centre as a contract R&D service provider with insignificant risks. These guidelines primarily focused on identification of the economically significant functions and consequently identification of the party that is engaged in their performance i.e. the Indian centre or foreign entities. The circular also included examples of the economically significant functions that are to be identified such as conceptualization and design of the product, providing the strategic direction and framework, etc. The guidelines also provided that the actual functions carried out and the actual conduct of parties be considered over and above the contractual arrangement. Hence, as can be seen from the above, Indian TP authorities had sought to provide a framework on the classification of the Indian R&D centres based on performance of economically significant functions, bearing of risks and providing of funding/ capital/ assets prior to the DEMPE framework announced by the OECD. Further, while the CBDT circular focuses on R&D centres of MNEs in India, DMEPE is a concept that has wider application as has also been analysed and explained in OECD.

Concept and importance of DEMPE

The concept of DEMPE was introduced by BEPS AP 8-10. DEMPE provides that (Para 6.32) the entities of the MNC Group that contribute to the functions related to the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation of the intangibles of the Group (which have been identified with specificity), owned assets and assumed risks in relation to the intangibles, should be compensated for their contribution to the DEMPE functions on an arm’s length basis (over and above other routine functions performed by them), post remunerating other group entities for activities performed. This guidance also clearly supports the concept of substance over form, by focusing and remunerating based on the actual functions carried out and risks undertaken, rather than being guided only by the terms of inter-company contracts.

The OECD provided guidance on the important functions that can be considered as value adding functions, since they contribute to intangibles and need to be identified and analysed for DEMPE. These include design/ control of research and marketing programmes, controlling the strategic decisions regarding intangible development programs, management and control of budgets, important decisions regarding defense and protection of intangibles, etc.

OECD guidelines 2017 (Para 6.34) has laid down a six-step framework for analyzing the transactions involving intangibles and to determine the arm’s length price for related transactions. These are as under:

- Identify the intangibles used or transferred in the transaction with specificity;

- Identify the full contractual arrangements, with special emphasis on determining legal ownership of intangibles based on the terms and conditions of legal arrangements;

- Identify the parties performing functions using assets, and managing risks related to DEMPE of the intangibles by means of the functional analysis;

- Confirm the consistency between the terms of the relevant contractual arrangements and the conduct of the parties;

- Delineate the actual controlled transactions related to the DEMPE of intangibles in light of the legal ownership of the intangibles, the other relevant contractual relations under relevant registrations and contracts, and the conduct of the parties, including their relevant contributions of functions, assets and risks;

- Where possible, determine arm’s length prices for these transactions consistent with each party’s contributions of functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed.

We know that conducting a robust Functional, Asset and Risk (FAR) analysis is the building stone of any economic and arm’s length analysis. OCED guidelines 2017 also emphasised on conducting and analysing detailed FAR analysis with a focus on DEMPE functions, to understand the value addition functions undertaken by each entity of the MNC Group. It has also been provided that it is not sufficient to go by contractual terms and arrangements agreed/ documented between AEs, but it is critical to accurately delineate the actual transaction to understand actual conduct of the parties to conclude on actual functions undertaken.

An important takeaway here is that in addition to the risks assumed by the parties in relation to the DEMPE functions, the control over the risks and the financial capacity to assume the risks in relation to the DEMPE functions, is also significant. Herein, right of decision making with respect to the intangible and financial capacity to bear the consequences of the loss arising out of said decisions, is required to be analysed.

The crux of the discussion is that if the legal owner of the intangibles does not contribute to the value addition functions in relation to intangibles, then should it be provided residual returns arising from the exploitation of the intangibles? Per this guidance, the group entities that actually undertake the DEMPE functions and assume and control the related risks, should be allocated a fair proportion of the residual returns attained by exploitation of the intangible assets.

An example of TP model of a limited risk distributors (LRDs) is worth a mention here. In case of a LRD model, the principal bears the majority risks of the business and the LRD is compensated basis an assured return on the limited functions carried out by it. Herein, a detailed analysis may be required on the functions carried out by the LRD because if it shows that a LRD is contributing significantly to any of the value drivers of the business for e.g. developing customer lists, marketing, etc. then a question may arise if a return higher than its limited functions should be provided to it.

TP methods

The OECD has also provided guidance on the selection of the appropriate TP method for economic analysis pertaining to transactions involving intangibles. Herein, it has stated that one-sided methods including the Resale Price Method (RPM) and the Transactional Net Margin Method (TNMM) are generally not reliable methods for directly determining the arm’s length price for contributions to intangibles as they usually allocate all residual profit to the owner of intangibles, after providing a limited return to those performing the relevant functions. Given the unique nature of the intangibles, OECD supports the use of Comparable Uncontrolled Price (CUP) method, transactional profit split method (PSM), such as valuation-based methods (e.g. discounted cash flow technique) depending on facts and circumstances of the case and availability of information.

UN manual perspective

The guidance on intangibles as provided by the OECD is also supported by the guidance provided by the United Nations (UN) Practice Manual on TP (2017). The basic principles guiding intangibles including concept and identification of intangibles, comparability factors to be considered, identification of important DEMPE functions, etc. as are contained in the OECD are further supplemented with appropriate illustrations in the UN manual.

HTVI – definition and determination of ALP

BEPS AP 8/ OECD 2017 has also introduced a concept of Hard-to-value intangibles (HTVI). Para 6.189 of the OECD 2017 defines HTVI as “intangibles or rights in intangibles for which, at the time of their transfer between associated enterprises, (i) no reliable comparables exist, and (ii) at the time the transactions was entered into, the projections of future cash flows or income expected to be derived from the transferred intangible, or the assumptions used in valuing the intangible are highly uncertain, making it difficult to predict the level of ultimate success of the intangible at the time of the transfer.”

The valuation of the HTVI is highly ambiguous since an accurate comparable uncontrolled transaction (CUT) is not available and a valuation on the basis of financial projections would be required, however, the probability of ultimate success/ failure of HTVI is unpredictable at the time of its transfer. Therefore valuation of HTVIs will necessarily be in the nature of an “Ex-ante” analysis.

In the present case, there may be significant differences between ex-ante and ex-post analysis arising out of a situation of unavoidable information asymmetry between taxpayers and tax authorities. The tax authorities, using information which can only be available after the event has occurred, may challenge the assumptions used by the taxpayer for determination of the arm’s length price of the HTVI at the time of its transfer. Typically, the OECD guidance is that if there are significant differences between ex-ante projections and ex-post outcome of the intangibles, and if the differences cannot be reliably explained by the taxpayer, then the tax authorities can challenge the arm’s length price determined by the AEs at the time of the transaction and also make a TP adjustment. However, given the unique nature of HTVIs, certain additional guidance on exemptions have been provided to the stakeholders:

- Situations wherein the taxpayers are able to substantiate with sufficient documentary evidence that the differences between the projections and the actual outcomes is due to enforceable events which are beyond control and could not be anticipated at the time of the transaction;

- Transaction is covered by Bilateral/ multilateral APA;

- Difference between ex-ante projections and ex-post outcomes does not result in increase or decrease in compensation by 20 percent;

- Difference between ex-ante projections and ex-post outcomes are not greater than 20 percent of the projections during commercialisation period.

Way forward and point of focus for taxpayers

With the introduction of 3-tier documentation under the BEPS regime, tax authorities have access to particulars such as details of global transactions, TP policy framework and distribution of economic substance. The master file also contains specific details related to intangibles such as the description of the overall strategy of the Group for development, ownership and exploitation of intangible property and the details of the entities engaged in these functions, legal ownership details, details of important agreements related to intangible property, etc.

Therefore, it can be expected that tax authorities may also focus more on the role of intangibles in the MNE group, including aspects like:

- Important risks and functions being undertaken and performed by each group entity

- The contributions made by different entities of the group to value creation, with an objective to bifurcate DEMPE functions

- Whether the form of the inter-company agreement is in sync with the actual conduct of the related parties?

Taxpayers have also recognised the increasing focus on TP aspects of intangibles and there is greater emphasis on delineating DEMPE functions and entities performing the DEPME functions and updating the TP policy as well as the inter-company agreements. As intangibles drive profits and questions around allocation of those profits, MNCs would need to maintain continued focus on regularly updating their TP analysis and documentation.

[1] DEMPE refers to development, exploitation, maintenance, protection and enhancement functions undertaken in respect of the intangibles of a group

COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a global economic downturn, impacting not only the demand side but also disrupting the supply chain — global as well as domestic. This has spurred stakeholders in the value chain, ranging from consumers, retailers, distributors, manufacturers to governmental agencies, to reconsider their operations and make requisite changes. While the impact of such changes is visible in the short run, this article attempts to evaluate key trends and aspects of the post COVID-19 period (“COVID recovery”) from a transfer pricing (TP) perspective.

Measures undertaken during the pandemic

The solution to a problem can be offered only when the nature of the problem is clearly deciphered. Applying this to the present context, implications arising from COVID recovery would essentially involve identification of various changes in the organisational, operational and transactional dynamics, deployed by enterprises due to the COVID-19 outbreak:

- Operational changes – Sudden global onslaught experienced due to the COVID-19 pandemic adversely impacted both the demand side as well as enterprises’ ability to cater to even the impacted demand. To address such changes, enterprises tried to implement several operational measures, targeted towards – (i) optimising their supply chain / operations, and (ii) increasing their reach to the customers:

- Re-organisation of supply chain– With lockdown in several key manufacturing locations, supply chains of the manufacturing entities were severely impacted. Enterprises started evaluating alternate sourcing locations/ suppliers, either as a temporary arrangement or even on a long-term basis. Enterprises which had centralised manufacturing/ procurements, evaluated alternate sourcing locations to mitigate risks associated with the failure of centralised sourcing. Other manufacturing enterprises with multi-sourced key inputs went on to evaluate mobilisation of secondary suppliers to ensure that sufficient resources were available for sustaining the supply chain. While still others considered creating “shared resource pools” which would help in ensuring the availability of critical raw materials to key manufacturing locations.

- Transition to enhanced reliance on digital sales channels – Restricted movement of consumers and social distancing norms lead to the traditional brick-and-motor sales channels shrinking. This disruption drove adoption and growth in online/ digital sales channels, which provided consumers a more secure shopping environment from the comfort of their homes. Such convenience steered growth in online shopping by consumers and led several enterprises to move their products to online / digital sales channels. Such movement also required digitising their product portfolio to provide online shopping. However, it still relied on establishment of physical warehousing to feed into delivery service providers.

- Work from home – A new order emerged with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic - ‘work-from-home’, ‘remote working’, ’video conferencing‘, etc. This new working arrangement was the immediate requirement for sustenance of most of the service companies. Recently several researches show that substantial portion of the workforce which responded positively towards the new working order, may continue with work-from-home. For instance a global research report by Lenovo of 20,262 workers worldwide, states that 74% of survey respondents from India may want to continue to work from home; more than they did before the COVID-19 pandemic.[1] Considering the short term and long term implications of such paradigm shift, industry players have expedited deployment of additional information technology (“IT”) tools and assets to ensure that the business continues with the same level of security and efficiency.

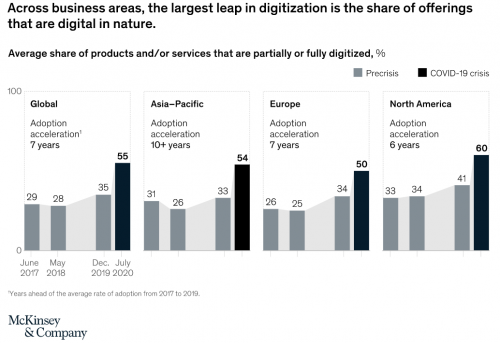

- Reverse outsourcing with the use of digital tools – During the pre-COVID times, there was an ever-increasing trend of outsourcing routine / mundane activities / processes to outsourcing service providers. This helped businesses in reducing their cost of operations and focus on core / critical activities / processes. However, it also made them more dependent on external factors and exposed them to disruption risk. With the experience gained from COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, several enterprises started to re-organise their processes / activities using digital tools such as artificial intelligence, robotics and automation. This was not only to provide business continuity and resilience for the enterprises for such an unprecedented time, but also to move for business reengineering which would give them more efficiency and sustainability. In this regard, it is important to highlight that a McKinsey report indicates how firms have taken a leap through partial or full digitisation in improving their products or services.[2] This report also shows that the COVID-19 pandemic has acted as a catalyst of sorts for ushering in technological revolution, which is seen across industries.

- Implications on intra-group transactional terms – With the sudden change in the economic and industrial circumstances, and considering the additional costs incurred and risks being assumed, several businesses, as a knee-jerk response to the COVID-19 pandemic, re-evaluated the transactional terms of their existing intra-group transactions.

- Identification and treatment of COVID impacted costs – With the operational changes in business (as discussed above) there were certain cost elements incurred by the enterprises that were idle (i.e. non-productive) or were extra-ordinary in nature. While manufacturing and distribution entities faced additional costs on account of complete cessation of business during lockdown, service entities were still able to continue with remote working by incurring additional enabling costs (such as costs for IT tools and remote working hardware) and idle costs (such as workspace rent and costs associated with lower productivity).

With changes in the mode of operation, costs earlier considered as normal (such as retail space and office rent) were no longer contributing towards value creation. The treatment of such costs, especially in the case of entities transacting with related parties was a key point of concern for several enterprises. Apart from this, as mentioned above, several enterprises also decided centrally to invest in digital tools to further streamline their business operations. While several enterprises centrally managed and funded such costs, in certain other cases, it was also seen that local costs incurred on account of COVID-19 was absorbed by the respective local entities.